Events and excursions, Winter 2018-19

The Maurice Barley Lecture, 10th November 2018

‘The Eleventh Hour of the Eleventh Day of the Eleventh Month: What happened next in Nottinghamshire? By Professor John Beckett

OTC Officers at the unveiling of the memorial at University College, Nottingham.

John Beckett posed an interesting and well-judged question in the title of his Maurice Barley lecture to the Thoroton Society, which was delivered on the eve of the centenary of the 1918 armistice. ‘The Great War’, as it was known to contemporaries, officially came to an end with the peace treaties in the summer of 1919. However, the guns fell silent at the time of the armistice, on the 11th of November 1918. Popular commemorations at the time rightly concentrated themselves in July 1919 - a national day of celebration and thanksgiving on Sunday 6th July, followed by an official peace-day celebration on Saturday 19th.

However, the armistice did not go unmarked. News reached Nottingham with barely half an hour to spare before the 11am deadline. It did not stop the local population marking the significance of the moment. Bunting and flags were hung, the bells of St Mary’s were rung out, a thanksgiving service was held at the Albert Hall and, in succeeding days, there was the closure of leading employers and schools.

The problems facing the country were commensurate with the scale of the fighting. The return of thousands of demobilised soldiers, physically and mentally changed through the experience of conflict, went hand-in-hand with wider social developments. The employment of large numbers of women in once-male bastions of industry suggested something of the wider transformation wrought by war. Women had fought and suffered for their country no less than men - a fact all too evident in Nottinghamshire, with the explosion at the Chilwell munitions factory during the final year of the conflict.

Chilwell had produced some 19m shells from 1916-1918, about half of the total of high explosive shells produced nationally. Men demobilised from front-line fighting and women from wartime service were thus faced with the challenge of finding new forms of employment. T C Howitt, demobilised in October 1919, began a 40-year career in the City Architect’s Department and left the new Council House (opened in 1929) as his abiding legacy.

Others suffered from what we would today recognise as post-traumatic stress disorder but which, during their lives, was played out through shell-shock and, in some cases, domestic violence and failed relationships. There were 451 disabled ex-servicemen on the books of Nottingham Labour Exchange at one point - but those affected by mental and physical scars were undoubtedly more numerous.

How was the county to represent and remember its debt to these men and women? A decision taken in 1915 meant that no bodies were repatriated to Britain. Men were buried where they fell, but after the war bodies were moved to cemeteries such as Etaples and Thiepval, close to the front where they had fought. The Menin Gate at Ypres provided (as it still does) an ongoing sign of collective commemoration, from the time it was unveiled in 1927. Locally, commemoration took the form of shrines in streets and doorways, rolls of honour (such as that at St Stephen’s, Hyson Green, naming some 200 people) and in commemorative structures ranging from the religious (churches, chapels and lych-gates) to the utilitarian (memorial halls, such as those at Bramcote and Chilwell. Some (very few) villages, including Wysall, Cromwell and Maplebeck, were ‘thankful villages’ - so named because all their young men returned home - but the act and costs and process of commemoration proved more divisive and contentious than one would perhaps expect. Some men are still unnamed on any memorial (a motivation behind recent centenary commemorative endeavours) whilst others found themselves memorialised numerous times (through no fault of their own).

Nottingham skirted the issue of a war memorial for the Market Square, as proposed in 1920, but Jesse Boot ensured that the Victoria Embankment memorial was unveiled on 11 November 1927, before the armistice was a decade old. Kipling, by way of Ecclesiasticus, found the words by which many memorials and gravestones remembered individuals - ‘Their name liveth for evermore’. But it was Laurence Binyon, in his poem ‘For the Fallen’, who found the familiar words which we use each armistice day. So it is that every 11th of November we say ‘We will remember them’. And we do.

Richard A Gaunt

The Neville Hoskins Lecture, 8th December 2018

Telford's Legacy: 200 Years of Civil Engineering in Nottinghamshire. By David Hoskins

David described his talk as not a presentation about the great engineer Thomas Telford. It is about the industry and profession, of which he was a figurehead and a great proponent, and the application of Civil Engineering in Nottinghamshire over the last 200 years.

He began, however, by outlining the history of Civil Engineering, which probably began with the great Egyptian structure we now know as ‘Cleopatra’s Needle’. Civil Engineers were first mentioned by the Romans, who developed the use of cement as a building material that was also employed by the Saxons and Normans.

Moving closer to our own time, famous engineers such as Newcomen, Watt and Brindley who were all informally educated, learnt their skills through ‘trial and error’ and experience. In contrast, their slightly younger contemporary John Smeaton, who amongst other things was responsible for building of the Eddystone Lighthouse, was more formally educated. In 1771, Smeaton with some colleagues founded the Society of Civil Engineers; the first engineering society in the world. After its founder’s death, it was renamed The Smeatonian Society for Civil Engineering and now functions as a discussion club for senior engineers. Initially, engineering was closely associated with the military, for example designing and building fortifications and engines of war. By the 19th century it was recognised that Civil Engineering was a separate discipline and that there was a need for a professional body. On 2nd January 1818, the Institution of Civil Engineers held its inaugural meeting and Thomas Telford was elected its first President in 1820. Telford’s influence led to the granting of a Royal Charter in 1828. The Institution now has in excess of 92,000 members world-wide.

Telford himself never worked in Nottinghamshire, but the work of his fellow-professionals can be seen throughout the county in its visible infrastructure, from railways to power stations, and invisible but vital systems such as flood defences and efficient sewers.

David then led us on a whistle-stop tour through some of the interesting engineering schemes that exist in our county, including:

- King’s Mill Viaduct. Originally built for horse-drawn ‘trains’ in 1817, it became a railway viaduct in 1819 which makes it the oldest rail viaduct in the county. It is now a public footpath.

- Mansfield Viaduct which straddles the town and is now the Robin Hood Line.

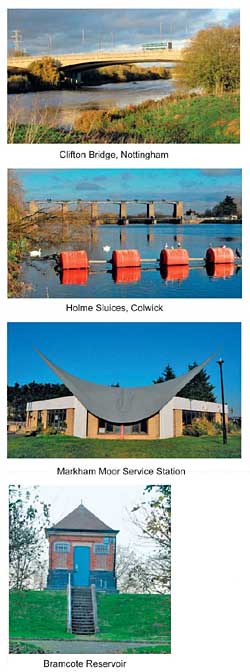

- A52, Clifton Bridge, which when it was built in 1958 had the longest pre-stressed concrete span. A second bridge, which mirrors the original, was built in 1972.

- Trent Bridge - that last of many that have spanned the Trent. It bears two plaques. One, dated 1868, commemorates the commencement of the work under the guidance of Marriott Ogle Tarbotton, Nottingham’s Borough Engineer who is listed as a Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers. The second plaque marks the opening of the bridge in 1872 by which time Tarbotton was a Fellow of the Geological Society.

- The many power stations along the Trent - Wilford, Staythorpe, High Marnham, Cottam, West Burton and Radcliffe on Soar - which have led to the nickname ‘Megawatt Valley’.

Civil engineers do not only build structures, they also alter, improve and adapt them to cope with the stresses that modern life places on them. The present bridge at Newark, originally constructed in 1775, was widened in 1848 to allow more traffic across. Close by, at South Muskham, are Smeaton’s Arches designed to protect the original route of the Great North Road from flooding. They were widened by about 4 metres in 1929. Engineers also change the use of structures. The Halfpenny Bridge over the Trent at Wilford was originally a Toll Bridge. It then became a footbridge and in 2014 was repurposed as a Tram and cycle bridge over the Trent, while Lady Bay Bridge, also over the Trent, has an almost opposite story as it was originally built in 1829 as a railway bridge but was repurposed in the 1950s as a road bridge.

Civil engineers are also innovators. In the 1920s when reinforced concrete was a new science, it was used to build Gunthorpe Bridge, though it was faced with cast stone. The depth of the arch of Fiddler’s Elbow Bridge, over the Trent at Newark, which for much of its length is only 8 inches is only possible because of this new material. Markham Moor service station, built in the 1960s, has a ‘gull-wing’ roof canopy which swoops from about 5ft to 37ft, constructed from reinforced concrete. A more recent innovation was the position of the tram bridge over the top of Nottingham Station. Built on Queen’s Road, the 104m long bridge was ‘pushed’ into position in 2013.

Many engineering structures are unseen. One of Nottingham’s earliest and most important engineers, Thomas Hawksley, was responsible for developing a pressurise water system which fed a network of reservoirs such as Papplewick, Bestwood, Bramcote and Bellevue (the latter is underground, at the top of Corporation Oaks). Marriot Ogle Tarbotton, already mentioned in relation to Trent Bridge, also created sewage works at Stoke Bardolph and similar facilities were built at Newark and Toton.

More recently, much work has been done to improve flood defences, for example, along the Embankment in Nottingham, where the apparently low flood wall actually extends to 5 metres underground. This depth is exceeded at Attenborough where the sealing wall is up to 8 meters below ground.

Attenborough is a good example of environmental improvements resulting from civil engineering work. The extraction of sand and gravel has resulted in the creation of wildlife and recreational areas around the county, not just at Attenborough but also Holme Pierpont, Colwick, Hoveringham and Rufford, not to mention the extensive playing fields on the Embankment.

After the talk, David answered a of questions ranging from queries about the structures he mentioned to the role of women in civil engineering today. Everyone agreed that his fascinating talk had opened their eyes to the part played by civil engineering in their everyday lives.