Papers read at visits and events

Stanford House: the owners

By Elizabeth Robinson

The first settlement in Nottingham was centred round St. Mary’s church, in what is now the Lace Market.

When the Normans arrived they settled on the sloping ground leading up to the Castle rock. The new settlement had a designated market place situated outside the castle walls. However, three weeks before the Battle of Hastings, Nottingham soldiers had marched north with King Harold to fight at Stamford Bridge. Instead of marching south with Harold after the battle they returned to Nottingham. Having no fear of the French, then, the people from the early settlement got on well with the French, and before long a joint market place was established in its present position, and the town could become one, although the two areas had separate administrations until about 1300. The most desirable place for a shop for business was around the Market Place, which meant that streets that were in a wonderful location, such as Castle gate, could become residential, with homes for wealthy inhabitants.

Two separate parishes had been established in the French borough: St. Peter’s and St. Nicholas’, and 19 Castle Gate is in the parish of St. Nicholas.

Once the Ducal Mansion was built, town houses were built in the ‘garden town’, and Castle Gate was one of the most fashionable streets. Go out of the front door [of 19 Castle Gate], turn right and the Market Place is nearby for shopping, socialising and business. Turn left, and it is a short walk to St. Nicholas Church. From the back of the house there were wonderful views to the east looking over the garden and paddock, across swathes of crocuses which coloured the meadows in the autumn and spring, to the Trent valley and the hills beyond. I grow the same spring crocus [Crocus vernus], and they are a tough little purple crocus, unaffected by the weather or the birds, and it spreads rapidly. Forbes Watson said:

It may be beautiful in the broad mid-day sunshine, but not with its full beauty. Go into the Nottingham meadows, where the plant grows wild, some warm afternoon in March, when the dreamy sun has just strength to unfold the petals, and look at the broad pale sheets of lilac bloom outspread upon the early grass, whose sweet young green is only just beginning to recover from the winter’s frost, the blooms here thin and scattered, hardly to be distinguished from water left by the retiring floods, and here with the dark green flowerless patches of Autumn Crocus [Colchicum autumnale]. (Flowers and Gardens notes on plant beauty. by Forbes Watson [brother of Watson Fothergill], John Lane: the Bodley Head, 1901)

This prime position meant that the occupants of the house were well-to-do, and occasionally very wealthy. A wealthy house owner wants fashionable house, and so the house was rebuilt or remodelled several times over the centuries.

The Eggington Family

The Eggington/Egginton family had owned a property here since 1587, perhaps even before that. In 1643 three members of the Eggington family paid assessments for this property in Castle Gate: ‘Mistris Eggington £1.10s., Brownloe Eggington £1 and Robert Eggington £1’.

Robert Eggington, the son and heir of Brownloe, was a Nottingham butcher (University of Nottingham online catalogue: Ja 179.); Brownloe Eggington came from London and was a tailor; Mary Eggington, a widow, was the mother of Robert. From 1626 to 1748 several of the Eggington family were Sheriffs of Nottingham, and there are references to Stephen and John throughout the eighteenth century.

In 1684 Robert and Mary Eggington sold the house to John Dand, Esq. for £110.5s. The 5s went to Mary. At the time of the sale the house was occupied by Joseph Holden, Gentleman.

In 1696 a brew house, wash house and other buildings were erected here, and this is probably the date that the house was ‘new built’ as mentioned in 1701, with John Dand actually living here.

John was the son of Rowland Dand, who had a large house and land at Mansfield Woodhouse (The antiquities of Nottingham Throsby). John and his wife, Mary, had three daughters: Margaret, Mary and Elizabeth. On the death of their father in 1701, these three daughters and John’s widow, sold the estate at Mansfield Woodhouse to John, Duke of Newcastle, and 19 Castle Gate was sold to Thomas Mansfield of Nottingham for £650.

The Bennetts

Thomas Mansfield sold the property to his son, Thomas Mansfield of West Leake. It was then sold to Thomas Bennett of Welby, Leicestershire, for £550, with Thomas Mansfield paying off £1,000 that was charged on the premises.

The town records show that in 1734 it was ordered that; Mr. Chadwicke, M. Abson and Mr. Storey have leave to put up Stoops and Rails before their houses in Castle Gate extending out into the street as far as Mr. Bennett’s and that Mr. Kirkby have leave to make Pallisades before his house about a foot from the same Ranging even with the corner of the two adjoining houses. Provided each of them pay six pence a year as an acknowledgement. (Internet: ‘Full text of the records of the borough of Nottingham being a series of extracts from the archives of the Corporation of Nottingham Vol. VI: 1702-1760. Published under the authority of the Corporation of Nottingham. Thomas Foreman and Sons. MCMXIV.). The house can be seen on the Badder and Peat map of 1744, marked as Mrs. Bennett’s house [No. 10 see below], for Thomas had died by that date. As drawn on the map, the house appears to have an open courtyard.

Mrs. Bennett died in 1751, and it is at this point that my particular interest starts. I am interested in the period between 1751 and 1756 because I think the exterior resembles a house at Barlaston by the architect Sir Robert Taylor. Taylor was the architect of Bromley House, built for Sir George Smith and his wife Mary Howe, and he also worked for Sir George Smith’s brother. A letter in the British Library from John Plumtre to the Duke of Newcastle is dated a week before the marriage of Sir George Smith and Mary Howe. (British Library John Plumtre to Newcastle, 12 Aug 1747, Add. 32712, f.372.) It is clear from the letter that the Dowager Countess of Pembroke arranged the marriage in order to obtain the support of the powerful Smith banking family. She managed the political interests of the Howe family until her death in 1749. When Mary Howe became an orphan at the age of ten she was asked to choose her guardian. She chose the Dowager Duchess of Pembroke, who was a relative she knew well, and obviously liked, and who was the aunt of Lord George Augustus and Captain Richard Howe and their siblings.

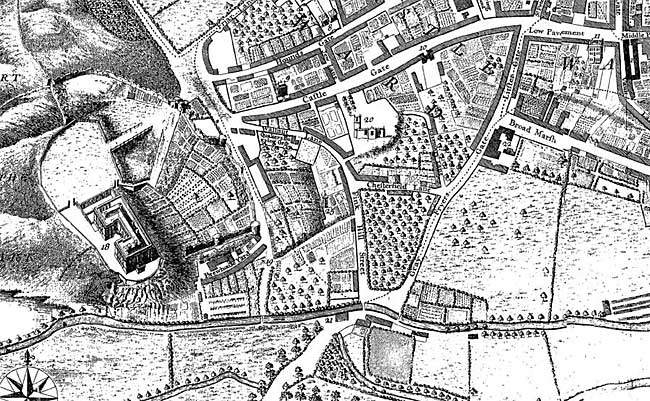

Badder and Peat’s map of 1744. Mrs. Bennett’s house is shown as 10 Castle Gate. Note the extensive gardens.

The Langar Connection

The closest relative of Mary Howe was Lord Howe of Langar Hall, and 19 Castle Gate was reputed to have been rebuilt in 1755 by Lord George Augustus Howe. Apparently the people of Nottingham called it Howe House, the town house of the Howe family of Langar. In Elain Harwood’s Pevsner Architectural Guide Nottingham (Pevsner Architectural Guides Nottingham, Elain Harwood, Yale University Press, 2008) she saysGeorge Augustus Howe built a ‘magnificent mansion” here in 1755 and in reference to the garden front writes: Pete Smith suggests that this front may have survived from Earl Howe’s House.

In 1755 George Augustus Howe was already fighting in America, he married Mary D’Aubigne in Virginia that year, but there were no children of the marriage. It is interesting that Richard Howe, the 4th Viscount was the second patron of Sir Robert Taylor. However, there is no documentation for Lord Howe building a house here, and it is a chaotic period regards understanding who is actually living in the house.

Chiverton Hartopp

In 1751 the house, and the estate at Welby, was inherited by Major Chiverton Hartopp, the nephew of Mrs. Bennett. Major Chiverton Hartopp was born in 1690 to Thomas Hartopp of Quarndon and Anne Bennett. He married Catherine Mansfield, the daughter of Thomas Mansfield of West Leake, at St. Mary’s, Nottingham on 14 February 1762. They had two daughters, Catherine and Mary.

The Corporation of Nottingham gave Chiverton the Freedom of the Town in 1740, because of his eminent service against the rebels in the northern part of the United Kingdom. In 1741 the Poll Book describes him as living in Woodhouse in Leicestershire (the village next to Woodhouse Eaves), and he does seem to have properties in both Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire. However, between 1747 and 1754 he held the prestigious post of Lieutenant-Governor of the Citadel, the great fortress of Plymouth.

The Citadel had been built by Charles II in order to protect the harbour from foreign invasion. There was no protection at all for the inhabitants of Plymouth who resented the building of the Citadel because they felt they had lost some of their land. The Governor was always a person of high rank, and, except in times of crisis when he assumed the role of Commander-in-Chief, was normally an absentee. From 1751 to 1759 the Governor was General Sir John Ligonier; one of the most experienced and respected soldiers in the country. Measured by the Governor’s salary, the Citadel was the principal fortress in the kingdom. (National Archives and book: Citadel: a History of the Royal Citadel, Plymouth, F.W. Woodward, Devon Books, 1987).

As Lieutenant-Governor, Chiverton Hartopp would have lived permanently at the Citadel, and was responsible for the day-to-day running of the establishment. In 1750, Hartopp enclosed with

fences the glacis of the Citadel. The glacis was a long gentle slope beyond the ditch which was kept clear of all obstacles; it starts at the crest of the parapet of the covered way, and its foot stretches out into the countryside. Once again the townspeople of Plymouth thought they had lost their land. The town’s constables imprisoned the sentry placed at the Citadel by Hartopp, and they petitioned that the Lieutenant-Governor be permanently removed.

In January 1753, General Sir Ligonier put the matter right when he and the Board of Ordnance wrote to the Corporation saying that the fences at the foot of Citadel Hill were to prevent cattle grazing, or too near approach of building, and did not lessen any rights or privileges that the town might subsequently claim. I suspect this hastened Hartopp’s return to Nottingham, and by April 1754 he is living in the house at Castle Gate, presumably for the first time. That is when he is recorded in the Poll Book as voting for Lord George Augustus Howe.

Church records show that later that year Chiverton and Catherine’s eldest daughter, Catherine, married James Modyford Heywood of Maristowe, Devon. The Nottingham parish register says: In this volume is recorded a marriage on 21st December 1754, solemnised in the house of Chiverton Hartopp, Esq., by Special License from the Archbishop of Canterbury [Thomas Herring] by Thomas Myddleton, vicar of Melton Mowbray, the vicar was a relation of the Hartopps. This is the only instance of a marriage by Special Licence to be found in the registers of the three ancient parish churches of Nottingham.

To bring you down to earth again, in 1755 Chiverton Hartopp was fined 6d for frowing Durt on [the] high ways in Cassel gate.

On the 16th February 1758 the Hartopp’s youngest daughter, Mary, married Captain Richard Howe of Langar Hall (famous for his victory on the Glorious 1st June 1794 when he was Admiral Howe) at Tamerton Foliot which is just north of Plymouth. Captain Howe was involved in various expeditions in the English Channel at this date.

On 6 July 1758 Richard Howe’s eldest brother, George Augustus, a Brigadier General in the British Army in America, was killed just before the battle of Ticonderoga. Richard then became the 4th Viscount Howe.

Major Chiverton Hartopp died at the age of sixty-nine on 2 April 1759. (I have not been able to discover the whereabouts of his will). By July 1759 the arrangements for the sale of the house were underway.

Without documentation it is difficult to know exactly what had happened over the last five years. I think that the house was remodelled by Sir Robert Taylor, for Lord George Augustus Howe in 1755, and that the ‘durt on the high-ways of Cassel-gate” was loose earth or soil from the building work. I would suggest that Taylor was responsible for the garden façade and the room on the left hand side of the ground floor as you enter. As a good friend of Lord Howe, there may have been an amicable arrangement for Major Chiverton Hartopp to use the house when Lord Howe was away.

A protégée of the Duke of Newcastle, the Rt. Hon. George Augustus Howe had stood as Member of Parliament for Nottingham in June 1747, when he was actually fighting in Flanders. During the 1754 election Viscount Howe was again one of the candidates. The electorate were lavishly entertained at Langar Hall for three weeks before the election. I would suggest that Taylor created the dining room so that it would be suitable for entertaining the electorate at future elections, and that is why it is on the ground floor. With its appropriate plaster work of grapes and vine leaves it is one of the largest rooms in the house. If eighteen Thoroton Society members can sit comfortably around the tables on computer chairs, it shows that the room could accommodate twice that number at election time. Situated on the ground floor it could be kept quite separate from the family rooms on the piano nobile. With the Smiths supporting the Howe family at election time, it makes sense that Nottingham town will be the centre of electioneering.

The will of George Augustus is short and simple; he leaves all his estate to his brother Richard Howe; there are no details of what this estate consists of. Richard Howe was adored by his family, and I believe generously included his brother-in-law, James Modyford Heywood in the sale of 19 Castle Gate and Welby, knowing the importance of the couple to his wife while he was away at sea. When Sir Robert Taylor built houses in Gradton Street, London, one house was occupied by Richard Howe, another by his mother and his sister Caroline and a third by James and Catherine Modyford Heywood.

William Stanford Elliott

Welby was sold to Peter Godfrey. (A Topographical History of the County of Leicester, Rev. John Curtis, W. Hextall, 1831). Sir Robert Taylor had a friend of that name, but I have not been able to establish if it is the same man. The house was sold to Valentine Stead, a merchant of Halifax, Yorkshire, for £2,450. His father was an apothecary in Nottingham, and he had married Ann, daughter of the Hon. Colonel Edward Pole in Nottingham in 1753. Valentine Stead died in 1761, but he stated in his will that his wife was to continue in his house in Castle Gate.

In 1775 Anne Stead sold all her father’s properties to William Stanford, a silk merchant of Brewhouse Yard, for £2,650. William was a royalist, and in 1789, when George III recovered from his mental illness and the town was illuminated, the decoration of Mr. Stanford’s house was impressive. He gave a hogshead of ale to all his neighbours so that they could drink the King’s health. (An Itinerary of Nottingham: Castle Gate and Stanford Street, John Holland Walker, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, No. 33, 1929).

William and his brother, Thomas, had been apprenticed to their uncle, William Elliott, who developed a superior method of dyeing and finishing black silk hose. The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1792 reported the death of William Elliott:

At Sutton, co. Lincoln, in his 88th year, Mr. Elliott, many years an eminent silk-dyer at Nottingham. When he began his business, he literally dyed his goods in a jug, and at his decease was supposed to have accumulated the sum of £100,000.

William Stanford continued and developed his Uncle Elliott’s business, going into partnership with his son-in-law, John Burnside. William Stanford changed his name to Elliott in 1796 in order to comply with his uncle’s will. William’s two sons also changed their names to Elliott.

William Stanford Elliott remodelled the house about 1775. The two marble fireplaces inset with Blue John stone resemble one at Thurgarton Priory, which was built in 1777. (The first marble chimney piece inset with Blue John stone was at Keddlestone Hall in 1760). William probably lived in the house until his death. In 1801 warehouses had been lately erected on the site of the stables and outbuildings. John Stanford Elliott died in 1823 and William Stanford Elliott, of Gedling House, in 1843. The house passed to their nephews, the Reverend John Burnside, rector of Plumtree, and William Stanford Burnside.

In 1853 a new street, Stanford Street, had been established immediately to the west of the house.

By 1851 a 43 year-old lace manufacturer, John Morley, had become a tenant of the house, although we do not know how long he was here. The house was unoccupied when the conveyance was drawn up on 29 September 1853, and the Burnsides sold the house to George Rawson, a solicitor, for £3,000.

A School and Commercial Use

Next a widow, Mrs. Treffry, moved her school for young ladies to 19 Castle Gate from Plumtre house. She had three girls of her own as well as twenty boarders aged twelve to seventeen. She stayed at Castle Gate until just after 1871, describing her school as Boarding and Day School.

As Nottingham became overcrowded and polluted, the beautiful town house became a place of business. In 1872 the house was sold to Joseph Spendlove, a Derbyshire man living in Sherwood, described as a manufacturer of muslin embroidery. He did not live in the house but used it as a warehouse, possibly also a workshop. He employed twenty men and forty women. His home was at 1, Clinton House, Standard Hill, but by 1901 he had moved to Lenton Fields, perhaps for fresher air. 19 Castle Gate was still his place of business in 1915.

From 1916 to 1925, and perhaps later, the house was owned by the lace manufacturers, L. E. & M. F. Ratcliff.

In 1928 it was bought by Robert Barber & Sons, solicitors, and it is at this stage that it was converted to offices. Robert Barber’s home was Sherwood Rise, and his father and son, both also named Robert, were solicitors. Robert died at the age of 77 in 1956, but the firm continued as Robert Barber & Sons until 2008.

Stanford House became a grade II* listed building on 11 August 1952 English Heritage Listed Building. 1 August 1952. English Heritage Building ID 454903) and is now owned by David Adjose of Exeid Locations and used as high class serviced offices after the building was restored which can now be appreciated once again.

The Howe Family

[The framework for this article was put together by Sue Kay, who was given a copy of the details of owners of the house in 1985 when she had cause to use the services of Robert Barber & Sons. This is mainly taken from deeds preserved at Stanford House and abstracts made by Miss Walker, Archivist to Central Public Library, Sherwood Street in 1962. I have added to this account.]

Stanford House was connected for some years to the Howe family. The following is a description of this family taken from ‘Men of Nottingham and Notts’ by Robert Mellors written in 1925.

In Langar Church a very questionable use is made of the transepts which are fully occupied with great tomb monuments, so that living people are entirely shut out, but however disposed we may be to complain, we stand in silent reverence before the tombs of the Howe family, resting in the South aisle.

THOMAS, LORD SCROOPE of Bolton, K.G., (d. 1609), and Lady Philadelphia, his wife, have a very stately tomb of black and white marble with their effigies, over which is a canopy resting on black marble pillars. He was “Lord warden of the West Marchses, Steward of Richmond and Richmondsh[ire], and Bow Bearer to all his Ma’ties Parkes and forests and Chases”.

SCROOPE, LORD HOWE, (d. 1712), was M.P. for Nottingham, and the inscription on a well executed bust portrait tells of how he remarkably distinguished himself in the preservation of the religion and liberties of his country when popery and arbitrary power threatened the subversion of both.

SCROOPE, LORD HOWE, (d. 1734), was Governor of Barbados. He is said to have “gained the respect and esteem that was justly due to a generous, wise, impartial, and distinguished Governor”.

GEORGE AUGUSTUS, VISCOUNT HOWE, (d. 1758), was the elder brother of the Admiral, and inherited the Langar estate, but dying first, the Admiral succeeded to the estate. He was M.P. for Nottingham. Under the North-west tower of Westminster Abbey is a monument, the inscription on which tells its own tale:-“The province of Massachusetts Bay in New England, by an order or the great and general court, bearing date Feby. 1st, 1759, caused this monument to be erected to the memory of George Augustus Lord Viscount Howe, brigadier-general of His Majesty’s Forces in America, who was slain July 6th 1758, on the march to Ticonderoga, in the 34th year of his age; in testimony of the sense they had of his services and military virtues, and of the affection their officers and soldiers bore to his command. He lived respected and beloved the publick regretted his loss; to his family it was irreparable”.

All the foregoing are eclipsed by the deeds, if not by the tomb, of the Admiral of the Fleet, Richard, Earl and Viscount Howe, K.G.

RICHARD, ADMIRAL EARL HOWE, (1725-1799) Langar. King George II said to him, “Your life, my lord, has been one continued series of services to your country”, and King George III gave to him on board his ship a sword and medal of honour. Both Houses of Parliament gave their thanks to him; the City of London have its freedom, and the nation its homage. He was made a captain at twenty, and took an active part in the Seven Years War. He was appointed a Lord of the Admiralty in 1763, and two years later was promoted to the important office of treasurer of the Navy. He was sent to defend the American coast, and later to relieve Gibraltar: became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1783, and received an English earldom in 1788. When war broke out with France in 1793 he had command of the Channel fleet, and on June 1st, 1794, he gained a great victory. He was given the Order of the Garter, received the thanks of both Houses of Parliament, and had other honours bestowed upon him. He was cautious, thorough, brave and considerate of his men, whom he made very efficient. In the family vault in the transept of Langar Church his remains were interred, and there was great sorrow at his decease, and a notable funeral. There is a monument to him in St. Paul’s Cathedral by Flaxman.

< Previous