News

NOTABLE PEOPLE: KEN BRAND

The Eulogy given by John Beckett at Ken Brand’s funeral

(Ken died on Monday 17th January, 2022, aged 89. The photograph below, provided by his wife Patsy, was taken on the occasion of him being awarded an honorary degree by the University of Nottingham.)

Ken Brand was my friend, colleague and mentor. I can say this despite the fact that, during the whole of the time we worked together he insisted on telling people he was Baldrick to my Blackadder! I don’t recall any cunning plans which went seriously wrong, but he was always keen to help with research, and to talk about his own interests. He was a bastion of the Nottingham Civic Society over decades, and for many years a Council Member of the Thoroton Society.

He was a lovely man. In the words of Hilary Sylvester, chair of the Nottingham Civic Society, he was ‘a warm and welcoming person’. Ken was born in Southampton in 1932 and remained a supporter of Southampton FC throughout his life. After National Service and teacher training he moved to Nottingham in 1957. The whole of Ken’s working life was spent teaching in Nottingham secondary schools, and he retired in 1991 as Head of Resources at Ellis Guilford School. He trained as a geographer but his teaching career was in mathematics. From the time he joined the Nottingham Civic Society in 1979 Ken’s interests were moving towards buildings. He was largely self-taught although he acknowledged the tutorship of Professor Maurice Barley and Keith Train, stalwarts in their turn of both the Civic and Thoroton societies, and local architects who played a key role in Nottingham's development, among them John Severn, Robert Cullen, and Julian Marsh. Ken’s output was mainly published through the Nottingham Civic Society. He wrote a series of booklets, which the Civic Society published, on The Park Estate, Mapperley Park, and the Shire Hall, but is perhaps best known for his studies of Nottingham’s two great Victorian architects, T.C. Hine and Watson Fothergill both of whom became household names.

The booklets were the tip of a considerable iceberg. He also published and wrote much of the Civic Society’s newsletter, developing it from a stapled A4 sheet to an illustrated book. Ken edited 101 issues over more than 30 years and he wrote much of the content. As if this was not sufficient for a man who was technically retired, he gave talks to local groups, led guided walks, wrote articles for the Nottingham Evening Post, gave talks on BBC Radio Nottingham, organised photographic exhibitions and generally went to great lengths to share his interest and knowledge as widely as possible with students, descendants of Nottingham Architects, owners of historic properties, and architects.

In 1996 he was awarded the Eberlin Prize for lay help to architects in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, while in 2008 Elain Harwood, in her volume for the Pevsner Architectural Guide to Nottingham, wrote of Ken that his ‘generosity of time and knowledge has been exceptional’.

From 1985 Ken ran the Civic Society’s ‘Mark of the Month’ scheme for building and environmental improvement. Despite his particular interest in Victorian architecture, he championed good modern development through the Mark of the Month awards. Local architects were grateful for such awards despite the involvement of an amateur. Ken became extraordinarily knowledgeable about Nottingham’s buildings and landscape, and he was always happy to share that knowledge. For the Thoroton Society Ken was a regular attender at winter lectures, and he reported regularly to the Society’s Council on Nottingham City Planning issues. His last publication was an essay on enclosure and architecture in Nottingham in the 1850s, a theme he and I first addressed in an article published in 1997 in Transactions of the Thoroton Society.

Beyond his involvement with the societies, Ken was a key figure in the Centenary History of Nottingham Project which led to the publication in 1997 of A Centenary History of Nottingham, and he and I wrote several other books and articles together designed to increase wider knowledge of Nottingham both locally and further afield. One of the books was a study of

the Nottingham Council House, designed by another of Ken’s favoured architects, Cecil Howitt. It seemed a great shame that there were no obvious ways of rewarding Ken for all that he was willing and able to do. Eventually we found a way, in fact two ways.

In 1997 Ken was awarded the prestigious title of Citizen of Honour by Nottingham City Council in its Centenary Year, in recognition of his contribution to our understanding of the history and built environment of Nottingham. Dorothy Ritchie, for many years a local studies librarian, recalls Ken telling her that ‘when he was made Citizen of Honour, he told me that somehow between the Council House and Radio Nottingham (on York Street in those days) the statuette was broken and the head came off. Ken was highly amused and did the interview with the broken award in front of him.’ Five years later Ken was nominated for and appointed Doctor of Letters, an honorary degree awarded by the University of Nottingham, for his contribution to the community (2002).

Ken was local lay adviser to the Civic Trust, and played a key behind-the-scenes role in the awards granted in 2002 to the University of Nottingham’s Lakeside Arts Centre, Jubilee Campus, and Millennium Garden. In the Evening Post he wrote that these awards represented ‘an achievement which reinforces the university's position as the prime patron of architecture in the Nottingham area' (30 April 2002). Ken lived a full and enjoyable life and everyone here today who knew him at all well will recall his sign off phrases: ‘just a moment’; ‘while I have you here’, ‘just before I go’ and ‘one final point’ - which usually meant another five. I do not begrudge him these foibles. They were part of his character, and in my experience those ‘final points’ were often the ones he really wanted to get over, and the most important. Ken was a lovely man, a good friend - despite his lifelong support for Southampton FC - and fantastically generous with his time - but you had to listen to those ‘final points’ to make sure you had not missed a gem!

John Beckett

REMEMBERING SOME OTHER NOTABLE PEOPLE

Elizabeth Hooton of Nottingham, a dissenter and one of earliest quaker preachers, died on 8th January 1672. Elizabeth was the first woman to become a Quaker minister.

Francis Willughby, was an ornithologist, ichthyologist, scientist and linguist. Although born in Middleton Hall in Warwickshire, the family seat was Wollaton Hall. He was an avid student and scholar. He and his associates were advocates of a fresh way of studying scientific matters which involved relying on observations, extremely radical in a period when students still relied on the ancients and the Bible for knowledge. He is commemorated by a plaque in Southwell Minster - he died on the 3rd July 1672.

Helen Kirkpatrick Watts, daughter of the vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Lenton, died on 18th August 1972 aged 91. Helen was a militant suffragette who was inspired by a speech of Christabel Pankhurst and subsequently, in 1907, she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union. During her suffragette activities she spent time in prison and was on a 90 day hunger strike in Leicester Prison, following which she received a Hunger Strike Medal. On November 22nd 2016, 100 years to the day after women were first able to vote in a General Election, a juniper tree was planted in her honour at Nottingham Arboretum.

Robert Parsons in 1572, 450 years ago, on 25th January, was drowned in the Trent near Newark. He was an eminent composer of the time and member of the Chapel Royal - a friend wrote of him “Parsons, you who were so great in the springtime of life, how great you would have been in the autumn, had death not come.”

Barbara Cast

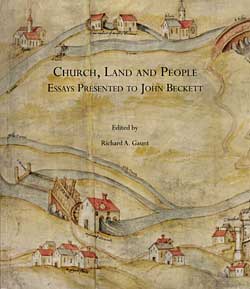

The Story behind John Beckett’s Festschrift

You may have noticed that it is the occupational hazard of historians and archaeologists to be constantly talking about dead people. The concept of a Festschrift offers a very welcome exception to that rule. A Festschrift is a volume of essays which honours a respected person, usually (although not always) an academic, and is presented to them during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the honorand's colleagues, former pupils, and friends.

The origins of John’s Festschrift was a conversation which I had with Rob James following the Thoroton Society’s Spring meeting and AGM at Kingston-on-Soar in 2017. We were discussing ways of commemorating John’s long service as an academic, and as Chair of the Thoroton Society, in advance of his retirement from both positions. By the end of that conversation, I had managed to volunteer myself to edit the book!

Two questions immediately presented themselves - first, who to ask to contribute? Second, and more crucially, how to keep it a secret (given that we had determined upon the Record Series as the likely publisher).

Fortunately, there was no shortage of potential contributors - the real difficulty was to find the right balance of friends, colleagues, and ex-students to contribute without making the volume skewed in one particular direction. I have no doubt that there were others who could have been asked to contribute, or included, but the book needed a theme, and contributors who would deliver quality pieces to schedule - both lessons which John had inculcated in his students.

Fortunately, the breadth of John’s work, the range of his interests, and the chronological spread of his publications, enabled a good coverage from the mid-1600s to the recent past. Finding a title proved problematic until I reflected that the core themes of John’s work might probably be summarised as the Church (particularly the Anglican Church), relationships with and use of the land, and people (both collective and individual).

Maintaining secrecy proved a constant worry for me. I had heard all sorts of tales of honorands who had found out about the book as it was in progress, sometimes seeking to affect the outcome by editing its contents or inviting (or disinviting) contributors. Other volumes had been advertised in publishers’ catalogues ahead of their appearance, thereby alerting the honorand before the volume was presented. And the occasional volume, regrettably, had turned from a Festschrift into a memorial volume by the time the publication appeared. I must commend my fellow contributors for the fact that they successfully maintained the secret, notwithstanding the fact that most communication was by electronic means. The only potential leak resulted when Michael Jones mistakenly wrote an e-mail to another Richard -fortunately, it was his own son, Richard Jones, who could be trusted to keep the secret. Richard is, of course, our recently appointed Managing (and History) Editor of Transactions.

Having got the volume published on schedule, in spite of the COVID pandemic, we were prevented from presenting it to John, as originally intended. The plan had been to surprise John with the volume at the end of the Cust Lecture, which was intended as his valedictory lecture at the University of Nottingham in 2020. Rather like ‘This is Your Life’, I was going to get the contributors to stand up as I revealed the surprise to him and presented the volume at the end of the lecture. COVID meant a rather more low-key presentation, at John’s office, just ahead of a landmark birthday. Fortunately, John survived the shock - indeed he was rendered uncharacteristically speechless by it - and he has subsequently reflected on the volume in a recent issue of the Society’s newsletter.

During this year, the Cust lecture was rescheduled and the Thoroton Society was able to act as host for an online event. This lacked the immediacy and ability to meet collectively, but it has been preserved for posterity on the Thoroton Society website as a video presentation and, thanks to a generous grant from the Cust Endowment Fund, we have been able to publish it as a special publication of the Society.

The Annual Lunch also marked the official launch of the Cust Lecture, a worthy sequel to the Festschrift and one which exemplifies the close relationship between the Society and the University which John has done so much to foster. We were delighted to finally - if rather belatedly - launch the two volumes together. They reflect our esteem and thanks for John’s contribution over many years as an academic historian who has been actively involved in the world of regional and local history.

I hope that my editorial introduction to the Festschrift captured something of John’s biography and his working methods as a historian. Whether or not John realised it at the time, he had made my life much easier by revealing far more about his life and career, than he was perhaps conscious of at the time. All that I will conclude by saying is how nice it was to work on a project regarding a living subject - and how nice it was to see that subject live to receive it!

Richard A Gaunt (Editor of John’s Festschrift)

NOTTINGHAMSHIRE CHURCH HISTORY: Averham St Michael

The church of Averham St Michael has long been thought to be of Norman construction, The earlier Buildings of England: Nottinghamshire volumes, for example, speak of the masonry proving the whole structure to be of this period. However, as long ago as 1980, the author found evidence in the tower that indicated a possible earlier structure. Following the re-hanging of the bells in 2012 the first floor chamber of the tower was opened out, making both access and proper inspection possible. This confirmed that the east wall contained a blocked, rubble-headed doorway that formerly gave access to the high level of the nave at its west end, along with evidence of a pitched roof line above with the walls below covered in a light orange mortar. The upper portion of the blocking was removed to allow the examination of the doorway through the entire thickness of the wall and a corresponding rubble head was found on the east side. The orange mortar was analyzed using Raman spectroscopy and compared with the white mortar pointing found elsewhere in the tower, this established that it is also found on the internal south wall of the tower. A chance discovery of a section of timber embedded in the wall at the north side of the roof line showed that this was the stub end of a former timber that lay exactly along the slope of the former roof. Radiocarbon dating of the timber has yielded a date of AD 1000 ±33 years at 93.7 per cent probability, thus proving that this phase of the tower is of Anglo-Saxon date. Detailed analysis of the exterior south wall indicates that there is a lower phase that might be even earlier in its date of construction. It is hypothesized that the tower was either a former two-storey western porch (eg. as at Deerhurst St Mary in Gloucestershire) or a tower-nave (eg. St Mary Bishophill Junior in York), with a now lost portion of the church lying further west. A paper describing all the analysis and findings has been published open access in The Antiquaries Journal (appearing in print later this year) and is available for free download at the following link: https://bit.ly/3K9cY9V

Christopher Brooke

The Nottinghamshire Origins of The Owl and the Pussycat?

Scofton Church and Edward Lear

Scofton church

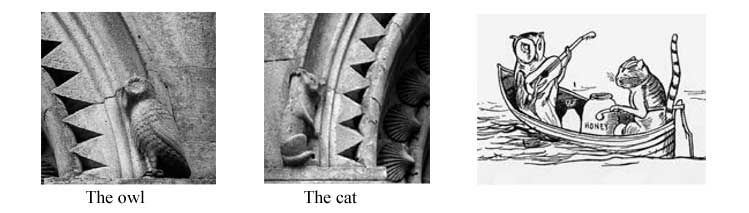

Scofton churchCreated over 35 years ago the Nottinghamshire Historic Churches Trust provides grant funding towards repairs and maintenance of local churches. While not large, NHCT grants help churches to obtain initial funding for projects or provide the final piece in the jigsaw of grants for works to be undertaken. The trust has aided works as diverse as roof replacements and stonework repairs to clock, bell and stained-glass window restoration. Along with grants from other charities and organisations, the trust relies on funding from the membership subscriptions of its “Friends”. NHCT Friends pay a modest subscription and in return receive an illustrated newsletter twice a year and are invited to three or four visits to Nottinghamshire churches. These visits are hosted by trust experts who lead a tour of a couple of historic churches and give an interesting and informative talk about the building, its architecture and its history; it is a most pleasant way to spend an afternoon. A Friends’ visit to Scofton church produced something quite unexpected, we found ourselves looking at images that seemed strangely familiar but not in a church context. Carved around the doorway of the main entrance to the church are a splendid pair of creatures, an owl and a cat, and immediately Edward Lear's nonsense poem on the owl and the pussycat who went to sea in a boat, sprang to mind, followed by the question, was there any connection between Lear and Scofton?

Did Lear get his inspiration from Scofton?

The church is built of ashlar in a neo-Romanesque style, and is dated by an inscription on the east wall to 1833. It was built by the owner of Osberton Hall as a memorial to his wife. Edward Lear's poem was first published in 1870, and had been written in 1867, so clearly the church came first, but did Lear know about it, had he perhaps seen the carvings? It is just possible that he might have done so. Edward Lear was a superb artist and draughtsman, as well as a writer of verses, and started his career making detailed drawings of birds for ornithologists to study. George Savile Foljambe, who built the church, was a keen ornithologist and his library contained books which Lear had illustrated. Foljambe was friendly with the leading ornithologists of the day, including John Gould, for whom Lear provided the drawings that were published in Gould's books during the 1830s. One of the features of Osberton Hall was the extensive collection of British birds in cases which was acquired by the first ornithologist in the family, Francis Ferrand Foljambe, who also founded the library to which his grandson, George Savile, added Lear's books. It would be fascinating to know whether the young Edward Lear was taken to Osberton to see the collections and meet with Foljambe, certainly John Gould stayed there. If so, then perhaps Lear saw the carvings on the church, and in later life when his thoughts turned to subjects for verses to entertain children, the image of the owl and the cat popped into his mind and the tale unfolded. The evidence has yet to be uncovered, Lear's papers are in archives in this country and in the United States, and there are 55 boxes of papers in the Nottinghamshire Archives Office relating to the Foljambe family. The answer may well be out there.

(Adapted from a Friends' article, written by NHCT trustee Dr Jenny Alexander.)

Cameron Bonser