Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

1816 – The year without a summer

1816 became known as ‘the year without a summer’ owing to the very cloudy conditions and lack of sunlight. The clouds were caused by a massive volcanic eruption in 1815.

The volcanoes

1816 was a catastrophic year for the population globally. There had been a succession of volcanic eruptions at the end of the eighteenth century, and three serious ones in the early years of the nineteenth century. These were 1812 – Mount Soufriere on the island of St Vincent. This eruption was recorded in a painting by JMW Turner, now in the Victoria Gallery and Museum, Liverpool1; 1812 – Mount Mayon in the Philippines; 1815 – Mount Tambora, on the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia. This is considered to be one of the most violent in recorded history. It began in April 1815 and continued for about five months. One of the best accounts of the eruption is found in the memoirs of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781-1826) who was stationed in Java for several years. Raffles despatched troops to investigate the source of the explosions, as he thought they were due to cannon fire.

It has been estimated that the Tambora eruption was some four times more powerful than the better-known eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. Vast clouds of dust and debris were flung into the stratosphere and covered the whole planet. This had the effect of preventing sunlight from reaching the earth’s surface, hence the ‘year without a summer’. There is evidence of global crop failures and widespread starvation. 1812 was also, to a lesser extent, a year with little summer.

This paper is an attempt to examine the effects of the Tambora eruption and the ‘year without a summer’ on Nottinghamshire.

The Meteorology

Accurate weather records from the first quarter of the nineteenth century are scarce. There are none from Nottinghamshire which contain the detail that I required, but there is a fine series of records from Derby2. The records are contained in a large bound book labelled ‘T and JT Swanwick Met Obs at Derby July 1793 to Nov 1838’, now in the possession of the National Meteorological Library, Exeter. They are remarkably detailed for the period and include daily maximum and minimum temperatures, barometer readings, rainfall and general comments on the weather.

The weather records were first kept by Thomas Swanwick from 1793 until December 1813, then by his son John Thomas Swanwick from January 1814 until November 1838: a remarkable series of continuous records covering forty-five years. Thomas Swanwick and his wife Mary were proprietors of a school, sometimes referred to as Swanwick’s Academy, in St Mary’s Gate, Derby. Their son John Thomas was a land surveyor3.

Temperatures

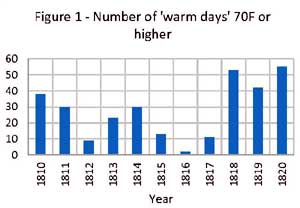

To assess the nature of the ‘summer’ of the years for which I had data, I checked the number of days in each year in the period 1810 to 1820 when the daily maximum temperature was 700F or higher. 700F was usually seen as the marker of a ‘warm day’ prior to the use of the metric system in meteorology (700F equates to about 210C). One would normally expect a day with a maximum temperature of 700F to have some direct sunlight to warm the air. The results are shown in figure 1. From this we can see that 1816 had only two ‘warm days’ when the temperature reached 700F or higher. Indeed, most days throughout the year are labelled ‘cloudy’ in the notes with John Thomas Swanwick’s daily weather records. 1815 and 1817 were also rather deficient in ‘warm days’, as was 1812 which suffered to a lesser extent from the two volcanic eruptions that year.

Rainfall

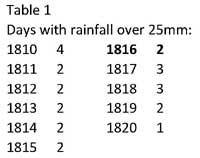

The rainfall of 1816 was largely unremarkable. There were two incidents of flooding in January, as recorded in John Holmes’ diary – see below. However, these may have been caused by very localized storms as no rainfall was recorded at Derby on the two dates mentioned (18th and 25th January). The severe rain of 12th April (34.3 mm, 1.35 ins were recorded at Derby) caused flooding on the Trent near Bleasby on Easter Sunday (14th April in 1816). However, the number of wet days (rainfall exceeding 1mm) in 1816 was 109, just a little above the average for the period 1810 to 1820 (102) and exceeded only by 1811 (114 wet days). Incidences of heavy rainfall in the East Midlands exceeding 25mm (1 inch) in 24 hours were, and still are, fairly rare, as shown in Table 1.

Effects of the Year without a Summer in Nottinghamshire

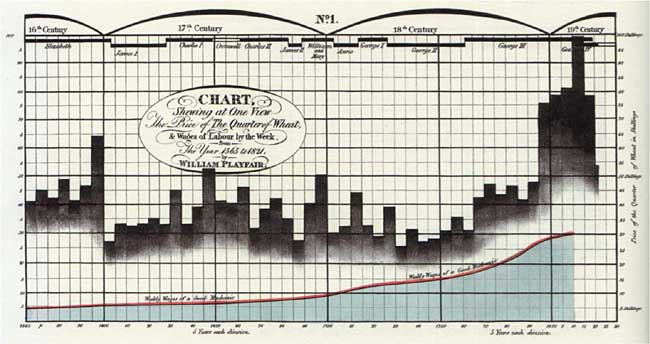

Figure 2. William Playfair's chart of wheat prices.

The Nottingham Date Book4, for 10th December 1816, records that ‘Owing to the scarcity of bread, good wheat readily realizing 140s. per quarter, there was much suffering and a great deficiency of employment. A public meeting on the subject was held in the Town Hall, the Mayor in the Chair, at which it was resolved to enter into a subscription for the relief of the destitute, not otherwise provided for. The amount raised was £4,184. In addition to this liberal amount, the London Association contributed twenty tons of red herrings, Lord Middleton gave three hundred tons of coal, and the Parish of St Nicholas expended £500 on a separate soup establishment. The poor-rates were also excessively heavy.’ The sum raised, over £200,000 in today’s money, indicates the extent of the suffering of the poor. The chart by William Playfair5 shows wheat prices per ‘quarter’ from the sixteenth century until 1821. This shows the great leap in wheat price in 1816.

Evidence from diaries

Sir Henry FitzHerbert of Tissington Hall in Derbyshire wrote in his notebook6:

‘This was the worst year, which was ever recollected. The spring was most severely cold, the snow falling as late as the 7th of June; and there was no grass till the end of June. The autumn was unusually wet, so that the Harvest throughout England was very bad, and in the higher parts of Derbyshire, the oats were not out till October, & in many places they were never housed, but remained in small stacks in the Fields all the Winter. Public Credit, which had been abused, was shaken; a great number of Country Banks failed, and several of the principal Mercantile Houses in London, and in the large Provincial Towns stopped payment. The Bank of England, as well as the Country Banks, which continued solvent, greatly contracted their issues; so that it was calculated, that the circulating medium had been reduced in quantity by fifty Millions. The Bank Restriction was stilled(sic) continued, and no gold coin appeared in circulation, & very little silver, & that of the most debased character. In consequence of all this, a third of the working population were thrown out of employment, and became Paupers.

In some Parishes near Nottingham and Mansfield, the Tenants threw up their occupations, the whole produceof their Farms being insufficient to pay their Assessments for the Poor. This state of things could not be without its moral effect; crimes of all descriptions increased fourfold, & the Prisons were crowded to excess’.

Samuel Curtis, Land Agent to Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne, wrote a long letter from Clumber Park to His Grace on 6th September 1816 to report on the affairs on the Duke’s estate7. He complained that ‘The weather has been for a week past worse than ever, in addition to wet every day we have had frosty nights. Tuesday morning it was so severe that it has nearly killed all the French beans and potatoe tops and I fear the Hops have suffered very much. On the whole I think we have the most impropitious season ever remembered, they have not begun harvest yet at Hardwick, suppose they will begin on the oats next Monday, there is a field or two cut on the forest lands but harvest will not be generally begun untill the latter part of next week. The Corn looks well where it stands up but much is laid very flat and must suffer...

... I sincerely hope your Grace and the Duchess will enjoy your trip on the Continent, the weather here is so unfavourable you need not regret your absence from Clumber’.

Nearer to Nottingham a farmer, whose name we do not know, kept a memoranda book from 1814 to 1848, detailing the regular happenings on the farm8. In the entries for 1816, he notes the lateness of the harvest and the length of time harvesting took to complete:

‘October 16 Finished getting wheat

October 21 Finished getting barley

NB began to mow barley 11 September so that we were six weeks all but one day from beginning to mow to the dry getting – a very wet harvest.

October 23 Finished getting beans, got all in Wednesday – began to mow them 12 September so that they were down six weeks’.

A gentleman resident in Bleasby, one John Holmes, kept a diary for many years9. His entries for 1816 included:

‘Two small floods happened at the beginning of the year; one on the 18th Jan and the other on the 25th. The month of Jan was mild and open, with very little frost. From the first of Feb to about the middle of the month, was very frosty, with but little snow. The month of March was windy, but dry; with gentle frosts.

A large quantity of rain fell on the 12th of April, which caused one of the greatest landfloods ever known, in this village; a large Trent flood followed on the 14th (being Easter Sunday) which did a deal of damage, by overflowing the new sown lands etc.... [The rainfall at Derby on 12th April 1816 was 34.3mm (1.35 ins). It is unusual in the Midlands to have a day of rain of more than 25mm (approx. 1 inch). See Table 1 above – Ed.]

The summer was remarkable wet; the hay in general got very bad, and the corn greatly damaged, by the long and constant rains; so that it was the latter end of Nov before the harvest was finished. The beans was almost rotten in the fields and a quantity of the barley sprouted. A small flood happened in Nov and another on the 17th of December ’.

Summary

The evidence from the diaries is of a very wet summer. However, the rainfall as recorded at Derby was not dissimilar from other years in the period 1810 to 1819. 1820 was exceptional in that it was a very dry and sunny year. I can only assume that because of the lack of direct sunshine in 1816, nothing dried out after rain and therefore crops remained wet. The lack of sun would also have delayed crop ripening, so that yields would be very low and grain prices correspondingly high.

Earthquake in Nottingham

To add to the general misery of 1816, there was a large earthquake in Nottinghamshire on Sunday 17th March. Earthquakes are not unknown in the County, but this incident was severe. The Nottingham Date Book records

‘Nottingham, in common with a great part of the North Midlands district, experienced a smart shock of earthquake. It was felt at half past twelve pm and as Divine Service, it being Sunday, was not over at the churches, great alarm was expressed by the congregations. At St Peter’s and St Nicholas’s, the consternation was so great that service had to be suspended for a few seconds, and one lady was borne out in a state of insensibility. The pillars supporting St Mary’s tower shook very visibly, but fortunately the attention of the crowded congregation was so engrossed by the eloquence of the Sheriff’s Chaplain, and the presence of the Judge and his retinue, that the alarm was but slight...

In many parts of the town and neighbourhood glasses were shaken off the shelves, articles of domestic use displaced, window casements thrown open and other indications manifest of the influence of the subterranean movement.’

John Holmes of Bleasby recorded in his diary:

‘On Sunday the 17th[March], the village and the surrounding county, for many miles, was thrown into the greatest consternation about half-past 12 o’clock, by a serious shock of an earth-quake. Divine service not been over at the parish church the congregation, (and myself) distinctly felt the undulation in the motion given to the building about three or four seconds. It being the Assize Sunday at Nottingham, the judge and his retinue being at St Mary’s church, it was perceived to shake very much.’

Notes

- Personal communication – Curator of Pictures at the Victoria Gallery and Museum, Liverpool

- Scans of the Derby records for the period 1810 to 1820 were kindly supplied by Mark Beswick of the National Meteorological Library and Archives, Exeter. The records are Crown Copyright and information extracted therefrom is used by permission of the Met. Office.

- The Directory of Derbyshire 1829, published by Steven Glover, records:

John Thomas Swanwick, Land Surveyor, St Mary’s Gate

Mary Swanwick and Son, gents’ boarding and day school, St Mary’s Gate

as by this date Thomas Swanwick (1754-1814) had died.

Glover’s Derby: The History and Directory of the Borough of Derby by Stephen Glover (1842) has a reference to “Swanwick, John Thos., Land surveyor, registrar of births, deaths, and marriages for St. Alkmund’s district, and agent for the Sun Fire and Life Office [at] 25, St. Mary’s Gate”. - Field, Henry (1884) The Date-Book of Remarkable and memorable Events connected with Nottingham and its neighbourhood.

- William Playfair is regarded as the ‘father’ of modern graphical methods of presenting visual data. In 1822 he wrote to parliament, enclosing the graph, as follows:

‘A letter on our agricultural distresses, their causes and remedies: accompanied with tables and copper-plate charts, shewing and comparing the prices of wheat, bread and labour, from 1565 to 1821: addressed to the Lords and Commons by William Playfair’

Source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Yale, www.brbldl.library.yale.edu. Accessed 25.2.2016. - Derbyshire Record Office D/239/M/F 10229 pp4-7. This can be accessed via https://recordoffice.wordpress.com/2015/04/10/a-volcanic-eruption/ . Accessed 25.2.2016

- University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections (UNMASC) Ne C 6396 Letter from Samuel Curtis to Henry Pelham-Clinton, 6th September 1816

- UNMASC MS 99 Memoranda book for a farm in the Stragglethorpe, Holme Pierrepont and Cotgrave area, Nottinghamshire 1814-1848.

- My thanks to Barbara Cast for drawing my attention to the diary of John Holmes.

John Wilson

< Previous