Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Nottingham 110 years ago: 1911 - a perfect summer?

The summer of 1911 started out like many summers do - with thunderstorms. On 1st May, temperatures had begun to rise, and by the end of May there were serious thunderstorms. On 25th May a band of storms stretched from Mansfield to the south coast of England. On 26th May, Stubton, near Newark, received 2.14ins (54mm) of rain, 9.6% of the annual average, in one storm. The worst of the storms were over the south of England on 31st May.

The summer became extremely hot and dry, one of the hottest and driest on record. Thursday 22nd June was the day of the coronation of the new king, George V. (1)

The day opened with damp and light drizzle, a disappointment after the sunny days of early June. The 34th Wimbledon season opened on the following Monday, 26th of June, with the traditional dampness, noted in the Daily Telegraph as ‘a familiar spectacle of sodden courts and idling players’. However, the weather soon became hot again, almost without change for weeks. August was particularly hot, with 9th August being the hottest day recorded to that date in the meteorological records. Nottingham Castle recorded a temperature of 94.6oF (34.8oC) on that day. This is the highest temperature ever recorded officially in Nottingham City. In 1968, the ‘official’ recording site for Nottingham was transferred from the Castle to the Watnall Weather Centre. Some people enjoyed the hot summer. Poet Rupert Brooke and his friends in the ‘Neo-Pagan/Bloomsbury axis’ (2) met at his home in Grantchester, near Cambridge, and held picnics and moonlight nude, mixed-sex bathing parties in Byron’s Pool by the Cam. Others were less fortunate.

In Ascot Week, early June, there were strikes in the docks. The entire crew of SS Olympic, moored at Southampton, went on strike along with the crews of five shipping lines and members of the Firemen’s Union. Later, in early July, theatres became so hot and stuffy that attendances at matinees fell away. People were taken to hospital with heat stroke. The weather had a bad effect on crops. Farm incomes fell and there was much anxiety. The pressures began to show, with increases of drunkenness in many villages present, as people used alcohol to ease their worries. By mid-July, temperatures were in the eighties. In Derbyshire, mill owners and quarry managers started the working day at 4.30am so that they could close in the early afternoon. The Times started to print a column headed ‘Deaths from Heat’. In early August the dockers, led by the firebrand union leader Ben Tillett, the founder of the Dockers’ Union, went on strike. The great London docks became silent, but for the dockers and their families it was a time of great hardship. Working-class housing, often insanitary at best of times, became unendurable.

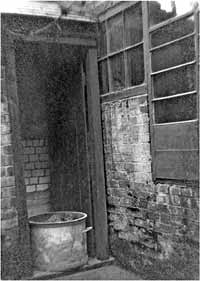

Pail closet

Pail closetNottingham in 1911 saw the greatest number of deaths from infantile diarrhoea of any year. There were no refrigerators and very few flushing lavatories. Pail closets were the order of the day. The pail closet in the picture served two houses, numbers 24/26 Denman Street in Nottingham. There was no back gate to the little yard and the full pail had to be carried out through one of the houses by the night-soil men when they made their weekly call to empty the pails. No wonder that over 400 infants in Nottingham perished from diarrhoea (3). Nowadays diarrhoea is simple to treat, with rehydration salts, but in 1911 there was nothing of this nature available. The August temperatures remained very high. Over the summer, Hodsock Priory in Nottinghamshire recorded thirty days with a maximum temperature of over 80oF (26.7oC). Agricultural work virtually ceased as the ground was baked hard, and there were shortages of water as wells began to run dry. The strikes at docks meant that vast quantities of imported foodstuffs began to spoil. To make matters worse, railway workers began to strike on 7th August, the Bank Holiday

Monday. The country was at a standstill. On 9th August, the Parliament Bill was passed, without the need for the King to create new peers. The bill prevented the House of Lords from blocking for more than two years any bill which had been passed by the House of Commons. By 11th August, Lord George Askwith, comptroller-general of the Commercial, Labour and Statistical Departments of the Board of Trade, had made progress with the many claims for increased wages and many wages were raised. This, along with the various benefits to be incorporated into Lloyd George’s National Insurance Act, ensured that many of the strikers went back to work.

By 23rd August, the weather station at South Kensington failed to register any bright sunshine for the first time in 53 days, and on 11 September the temperatures across the country dropped by an average of 20oF. Thus ended one of the longest and hottest summers on record in the United Kingdom.

Notes

1. King George V came to the throne at a time of constitutional crisis. In 1910, a bill by the Liberal government to provide rather basic pensions and social security for the poor was opposed by the House of Lords, whose Tory majority would be the people on whom the taxation would fall to pay for the provisions. The new king agreed to create sufficient Liberal peers to defeat the Tories in the Lords and pass the bill. An election took place in December 1910, as a result of which various bills proceeding through Parliament failed. One of these was a measure to allow women the vote. The loss of the bill infuriated the Women’s Social and Political Union - the Suffragettes. Their protests, which had so far been fairly genteel, thereafter became violent. Is it possible that the very hot summer of 1911 was a factor in this?

2. Friends of Rupert Brooke at the time included Hugh Dalton (Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1945 Labour government, who had to resign following a leak of Budget secrets); Lytton Strachey, writer and literary critic; Rose Macauley, novelist; Geoffrey Keynes and his brother John Maynard Keynes, economist (think Milton Keynes with concrete cows and roundabouts); George Mallory (died on Mount Everest); Virginia Stephen, writer, who married Leonard Woolf.

3. J.Wilson ‘And many of the little ones died’ - Public health, sanitation and weather in early 20th century Nottingham. Transactions of the Thoroton Society 2012 vol. 116 pp 129-139. Further reading: Juliet Nicholson, 1911: The Perfect Summer. John Murray 2006

John Wilson

< Previous