Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Instincts and experience of 1930s Nottinghamshire borstal design

(validated by modern research)

By Jeremy Lodge

Marching towards the Magna Charta public house, Lowdham. No stopping here! W. W. Llewellin is front and centre. T. C. Cape to his right. Both are referred to later.

Marching towards the Magna Charta public house, Lowdham. No stopping here! W. W. Llewellin is front and centre. T. C. Cape to his right. Both are referred to later.In May 1930, Lowdham Grange Borstal (6% miles as the crow flies north-east of Nottingham City centre) was opened following a 10-day, 130 mile march of officers and lads from Feltham in Middlesex. They were to live in tents, then huts on a hilltop site whilst they built the Lowdham Grange Borstal Institution and associated officers houses.

In January 1929, soon after the Treasury agreed to fund a new Borstal Institution, a committee of Alexander Paterson, Colonel Rogers, Paterson Owens (Governor of Feltham) and W W 'Bill' Llewellin (nominated Governor of the future Lowdham Grange) proposed:

- A building on the lines of a large public school with four self-contained houses, each under a housemaster.1

- Houses laid out either side of an administrative block, with other buildings surrounding a large enclosed quadrangle/drill ground based on Sir Aston Webb's Christ's Hospital School, Horsham.

- No central dining hall - boys should live and associate within their house.

- Subways connecting the central kitchen to buildings (and for cabling and piping) on top of which would be a covered way for communication and to form a secure boundary for the quadrangle.

- Building the Borstal will be the main activity of the inmates in the early years, to provide training and reduce building cost by one-third.

- Skeletal steel framed buildings, to create a template for the boys under training. Private contractor would erect the steel frames and construct the roof. The rest of the building work and installations would be undertaken by the lads under training supervision of local tradesmen.

- Small self-contained dormitories, not the individual sleeping rooms of existing Borstal.

It should be noted that this was a bold experiment. Lowdham Grange was to be an open borstal where, to quote its second Governor C T Cape "there are locks on doors but I do not know where the keys are ..."2 This was also a risky venture so far as security was concerned. So, their initial proposal (4th point above) was that the buildings should be arranged so that if the experiment failed, then the establishment could be made secure (see diagram below).

Within a short space of time their proposals for the layout of the buildings changed as confidence in their experiment grew. However, the internal design of the houses and their outward looking layout did not. H1 to H4 in the diagram below are the Houses. Facing south, with wide ranging rural views through Georgian style windows, are all of the communal living areas.

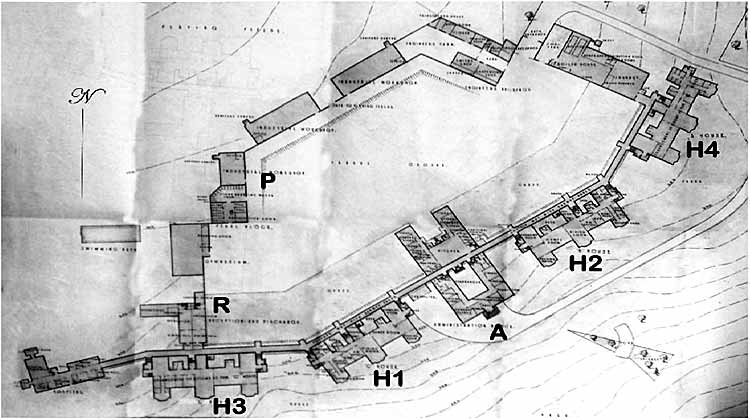

Proposed layout, 1930.3

Proposed layout, 1930.3The buildings were all aligned along the hilltop ridgeline. Being a two farm establishment, a Ha-ha (as found in many country houses) was built beneath the ridgeline to keep the animals out without interrupting the views or to suggest a security boundary (which it was not).

In the proposed layout on theplan above the contour lines can be seen to the bottom right, the main line of buildings sitting on the ridge line.

A is the administrative building above which stood a clock/water tower.

H1 - H4 are the Houses, numbered in the order that they were built. Between the Houses is a covered walkway. To the left is the hospital.

R is the reception block with individual lockable cells, to facilitate the acclimatisation of new arrivals. This was to be of a traditional design with six cells on two external sides of an oblong building (total 24) and a central gallery that we still see in many larger prisons.

P is the secure penal block with six cells, a secure yard and workshop with stone breaking boxes.

The planned arrangement of the gymnasium (between R and P), the industrial training workshops, laundry, plant rooms, etc, include adjoining walls to make the site secure.

With a swift development of confidence in the 'open' regime the layout of the support buildings, but not the accommodation, was changed and retained until the Borstal regime was closed in 1982 and the buildings demolished in the 1990s.

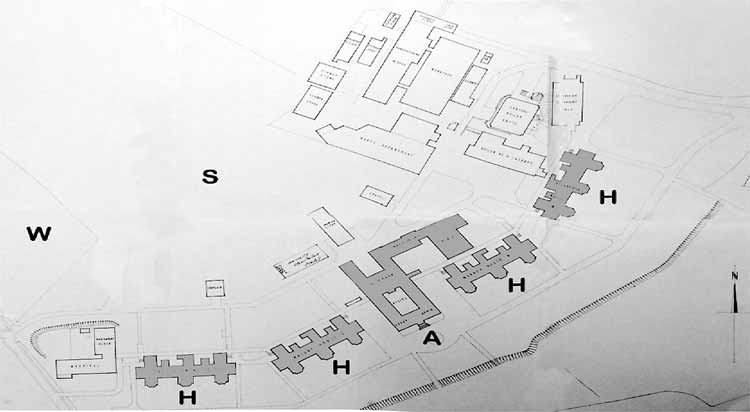

Final layout. 1980.

Final layout. 1980.S = Sports Field. W = Woodland.

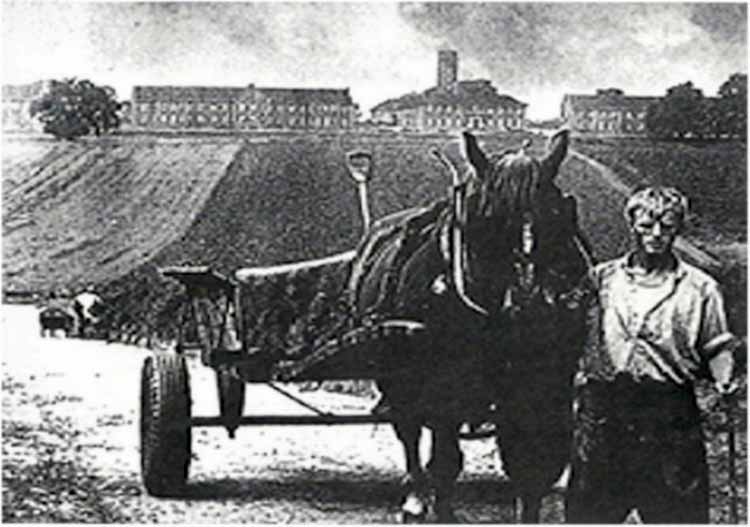

Uninterrupted view across the valley of the Cocker Beck from the Administration building. This view was shared by all dormitories and communal areas of the four houses. Also, of the officer’s tied house where the author lived. Photographer unknown, 1930s.

Uninterrupted view across the valley of the Cocker Beck from the Administration building. This view was shared by all dormitories and communal areas of the four houses. Also, of the officer’s tied house where the author lived. Photographer unknown, 1930s.

Looking back at the Administration building. Administrative building with tower and the full view of a completed house. Photographer unknown, 1947.

Looking back at the Administration building. Administrative building with tower and the full view of a completed house. Photographer unknown, 1947.

A completed house. Photographer unknown, 1930s.

A completed house. Photographer unknown, 1930s.One impact was noted by Lowdham Grange's first Governor W. W. Llewellin in 1933, when he wrote:

'The buildings, erected by the boys under expert guidance, stand on high ground, amidst trees and green fields, with wide views of a beautiful district of Nottinghamshire. Many visitors, arriving with preconceived ideas of a Borstal Institution, believe that they have come to the wrong place. There is an absence of any form of external constraint. There is no surrounding wall; there are no window bars; no boy is locked in.

The surroundings strike the note of trust. The restraints are internal.'

By internal, he meant psychological as he then discusses 'new spirit and traditions ... the aim is to build upon the sense of honour and loyalty inherent in every British boy'.

There are several key design decisions from the earliest 'Paterson-Rogers-Owens-Llewellin' discussions which aided this regime including

- the Houses were based on communities of 12 in a dormitory, 5 dormitories to a house to provide small, almost family sized groups

- from the first plan, the front of the Houses, the dormitories and communal areas face south to maximise natural light and optimise views.

The Paterson-led team designed the physical and psychological regime based upon their practical experiences of life and living in various communities, not least of Army life in the Great War (Paterson was an Oxford University Sociology graduate who had lived for many years in the slums of Bermondsey and had served as a Sergeant on the Western Front, Llewellin had been a Major in Mesopotamia). All, obviously had experience gleaned from their work in and with the Prison Service. I was recently struck how closely modern academic research and proposals reflected and confirmed (if unacknowledged) the collective instincts of Paterson, Rogers, Owens and Llewellin in 1929 when they were planning their practical and successful experiment that was Lowdham Grange Borstal Prison Design Today.

There are many recent principles being proposed, debated and recommended as good design practice for today's prisons that were a feature of Lowdham Grange and the Gladstone Report.4

For example, Al-Hosany and Elkadi identified a number of contemporary design attitudes including:5

| Modern Thought | Lowdham Grange 1930 | |

| Division into sections for small groups of 12 persons | Houses of 60 divided into dormitories of 12. | |

| Different premises to give space for different activities | Separate Games and Dining Halls, Library and a 'Blues' Room. Dormitories upstairs in each House. Association and House Administrative areas downstairs. | |

| Classrooms in the Administration Block, separate Kitchen, Gymnasium, Medical etc. | ||

| Healthy indoor environment including light and view. A recent project 'Creative Prisons' asked prisoners to design their own prison; more air, light and clear views featured strongly.5 | The main axis of each house was southerly with prodigious opening window space. Open and distant rural views. No visually constricting fences or walls. Functional changing rooms, bathrooms, sculleries etc on the less windowed north side. | |

| A Humane element placed at the centre of prison design. | "All the doors have locks but I don't know where the keys are" is a psychological as well as a physical and cultural statement.6 | Jana Soderlund and Peter Newman considered the new concepts of biophilic design in enhancing mental health in prisons which includes.7 |

| Light, fresh air, airflow, light, variety of views. | See above | |

| Soothing sounds of nature, variance in light, colours and nature scents | Buildings took advantage of their natural surroundings including being placed on the crestline of a hill. | |

| However, natural sounds (e.g. nocturnal animals and birds), countryside silence or farming scents proved not to be soothing for some former city dwellers. |

Dominique Moran, Yvonne Jewkes and Jennifer Turner stress that spaces affect the way that people act and like Wener they consider that the design process is 'the wedge that forces the system to think' through its processes and approach.8 Two key elements they highlight as good design practice are:

| Modern Thought | Lowdham Grange 1930 |

| Maximum exploitation of natural light and views of nature/exterior views through vista windows without bars. | See above. Not vista windows but Georgian paned and opening. |

| Human scale, connected pavilions | See above Units of 12 x 5 in 4 houses. Covered walkway for inclement weather. |

A recent newspaper report on a forthcoming open prison included in its description that it will be 'without bars to make it more "like home" for inmates in smaller more intimate wings for just 20 inmates rather than 60 in traditional jails ...which would make it conducive to rehabilitation'.9 Architect Simon Henley at the 4th International Space Syntax Symposium in 2003 proposed a 21st Century Model.

Prison where the architecture and the resultant building would be positive enablers.10

He spoke of a new model, developed in conjunction with the Prison Service, which included:

- maximum size 400 prisoners

- prisoner to live in a semi-autonomous unit, a house, within which he is a member of an accountable group, living close to open space

- He quotes the Home Office Design Briefing (1989) advocating groups of 50-70, although he stated that there is no evidence to ratify the efficacy of this figure

- Some prisoners work in the community during the day and return to their cells at night, which is essentially the approach of closed and pre-Lowdham borstals.11

Elwick et al, when considering UK and International comparisons, included eleven key aspects of good practice for improving the outcomes for young offenders. Although not acknowledged eight of these were part of the Lowdham regime including:12

- custodial staff involved in education (including life and social skills) which should be placed at the heart of an institution's focus

- interventions must be personalised and targeted

- institutions must be sufficiently small in size to properly cater for their residents, split into units, e.g. 40 beds divided into units of 10

- reintegration into the community must be a focus with activities in the community as a key aspect of provision

A recent US Handbook of Correctional Institution Design and Construction noted the interdependence of philosophy and design stating:

'So long as a prison resembles an impregnable fortress, the administrators therefore cannot avoid acquiring, to a certain extent, a "fortress psychology, and becoming primarily absorbed in the jailing function, to the neglect of the rehabilitative ideal.'13

which aptly reminds us that the building acts upon staff as well as their charges.

Juxtaposition of Borstal and staff housing, 1964.

Juxtaposition of Borstal and staff housing, 1964. Ordnance Survey - edited. The Administration building and the four houses are shaded. Note the close proximity of Woodland to the left, next to which and behind the Institution buildings were the sportsfields. The righthand side of the image shows the layout of the officer’s estate of tied houses.

We can see in the final layout the constituent parts remained true to their initial design principles. The initial proposed layout reflected security (potential failure of the open concept) fears thus conformed to existing practice, then with experience the layout unfurled taking advantage of the opportunities provided by the site, experience and increasing confidence. Even historian Dennis Mills unwittingly contributed to the discussion when he highlighted the concept of community, stressing the 'importance of smallness of scale'. His proposition was that communities are face-to-face groups, residing in close proximity to each other, thus having a mutual comprehensive knowledge.14 Certainly, until the late 1960s, the two communities - staff and their families and the lads, lived in close proximity with the lands working around both the officers and Institution estate. There were also regular scheduled family visits for social evenings in the House that their father was assigned to.lt was common to see children being carried aloft or riding in work barrows pulled by the Borstal lads. There were also sports days, concerts, film nights and other 'mixed' events. Children roamed freely (if not always as allowed) around the woodland and fields and accompanied Borstal sports teams to outside fixtures etc.

For both staff and those in their care, before the common ownership of the motor car, Lowdham Grange was considered a posting of inconvenience. The buildings and cultural regime were aligned. The resultant culture depended on the qualities of the staff, the response of the boys and also the acceptance, support and involvement of the local community which highlights that good architecture providing impressive accommodation and environment is important but not enough.

Jeremy Lodge,

Thoroton Society Member

References

1 Note, no mention of public schools in the Gladstone Committee discussions but reminiscent of the Redhill Farm Colony. One can see how Warder and Wilson came to their Public-School based conclusion, but as we have seen the pedigree behind this statement goes much deeper than this descriptive term.

Ibid. Warder & Wilson. British Borstal Training.’ p.118.

2 ‘Trusting the Boys’ Sheffield Telegraph. 1st May (1934). Deputy Governor Cape at Sheffield Rotary Club.

3 National Archives PRI COM 9/55 Treasury T161 1180 annotated for this dissertation.

4 Report from the Departmental Committee on Prisons (Gladstone Committee Report). 1895.

5 Aitch. I, ‘Build your own Prison.’ New Statesman, 5 February. (2007). pp.42-43.

6 Ibid ‘Trusting the Boys'. (1934).

7 Soderlund. J, Newman. P, ‘Improving mental health in prisons through design.’ The Prison Journal. Vol 96 (2017). Biophilic = human innate need for nature.

8 Dominique Moran, Yvonne Jewkes and Jennifer Turner (2015). Prison Design and Carceral Space. <figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/chapter/Prison_Design_and_Carceral_Space/10148543/1> [accessed 25 July 2024].

Wener. R.E, The Environmental Psychology cf Prisons and Jails: Creating Humane Spaces in Secure Settings. (Cambridge: University Press. 2012).

9 ’ Hymas. C, 'The first British jail where there are no bars on the windows will open in 2021’ The Telegraph. 1 May (2019), Politics, <www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2019/05/01/first-british-jail-no-bars-windows-will-open-2021/> [accessed 29 June 2019].

10 <www.spacesyntax.net/symposia/4th-international-space-syntax-symposium/>

Henley. S, The 21st Century Prison.

<www.spacesyntax.net/symposia-archive/SSS4/fullpapers/03Henleypaper.pdf > (2003). [accessed 29 June 2019].

11 A pattern used in the 'closed' borstal system where lads were in secure conditions overnight and open borstals where they were brought back to the institution but not under lock and key

12 Elwick. A, Davis. M, Crehan. L. Clay. B. (2013) Improving outcomes for young Cjfenders: an international perspective. CfBT Education Trust, pp.3, 24.

13 Flynn, F [review] ’Handbook of Correctional Institution design and Construction.’ (US Bureau of Prisons). Social Service Review. Vol 24. No. 4. (1950).

14 lbid. Mills ’Defining Community.’

< Previous