Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Nottingham Castle archaeology:

The Great Chapel and burials

By Gareth Davies

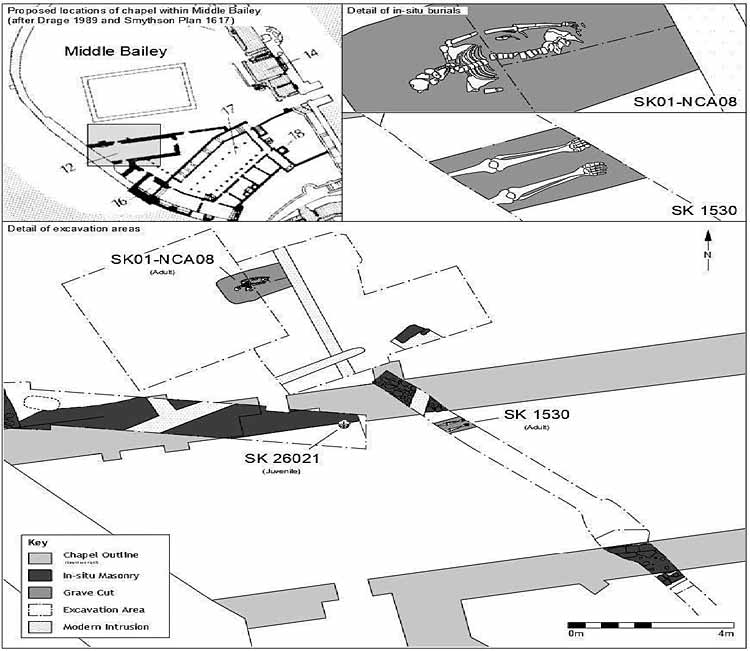

Some particularly interesting findings were made in the Middle Bailey of the Castle, including on the site of the Great Chapel. During the 14th century significant sums of money were spent on Nottingham Castle. The Middle Bailey is highly re-developed during this time, and one important element, known from documentary evidence, is the installation of the Great Chapel. This building is depicted on the Smithson plan of 1617. In the area of the Chapel, the upper half of a burial had been excavated in 1978. This was at the time thought to be a Civil War casualty, but it remained a bit of a mystery.

As part of the redevelopment project, Trent & Peak were asked to excavate the remaining shallowly buried half of the burial, so that it wasn't damaged during the groundworks. Pottery finds and radiocarbon dating of the bones gave a 16th century date, so this burial was not a Civil War casualty. However, it raised intriguing questions about later use of a burial ground around the Great Chapel.The redevelopment works also gave the archaeologists new opportunities to explore the question of the Great Chapel in this part of the Castle. Part of an additional burial was located just south of a portion of east to west aligned wall that aligned very well with the Smithson plan projection of the chapel. A further parallel wall located to the south was also observed in a service trench excavation, giving some confidence that the chapel has been located. The identified burial was that of an older male. The archaeologists were able to preserve the burial in situ, but an osteological assessment demonstrated that the individual had been buried in a shroud and then in a coffin. One interesting bit of pathology identified by the osteologist was evidence for patellar tendonitis, commonly known as runner's knee, and often associated with heavy lifting and sustained muscle use.Just north of the in situ adult burial, a disturbed juvenile burial was also recovered, again within the presumed chapel interior, almost abutting the northern wall. This individual returned a radiocarbon date of the 14th to 15th century,somewhat earlier than the burial excavated in 1978. The identification of burials within the presumed Great Chapel interior may imply high status individuals, whilst the later burial to the north may suggest a longer lived but less intensively utilised burial ground.

The excavations of the great chapel in the middle bailey highlight that the castle had transformed from a strategic fortification and military stronghold into a complex site and household with functions including the servicing of religious life and administration by the later medieval period.

Gareth Davies, Head of Archaeology, York Archaeological Trust

Castle Burials

By Scott Lomax

The two human skeletons found during the castle redevelopment, and the likely Tudor individual first discovered in 1978 and fully exhumed in 2016, are just some of the many human remains found at the castle over the past 240 years and it is highly likely that there are numerous burials yet to be discovered.

In the 1970s the tibia of a child estimated to have been aged 12-14, was found during archaeological works in the Middle Bailey, indicating that at least one further individual was buried near the chapel. Landscaping works after the castle’s destruction in 1651 appear to have disturbed the remains. The rest of the skeleton may still be within the site.

In 1927, following demolition of the Drill Hall which stood on Castle Road to the south of the gatehouse bridge, on the course of the external moat of the castle, labourers found the skeleton of an adult male estimated to have been aged between 30 and 35. The skeleton was found within the ditch, at a depth of between 6ft and 8ft. The bones were well preserved, with the teeth described as being in a ‘perfect’ state of preservation, but few other details are known.

An extract from the Badder and Peat map (1744) showing Nottingham Castle and its environs. The site of the 1927 discovery and Derry Mount are shown (labelled as 1 and 2 respectively)

An extract from the Badder and Peat map (1744) showing Nottingham Castle and its environs. The site of the 1927 discovery and Derry Mount are shown (labelled as 1 and 2 respectively)The Northern Bailey of the castle is too often forgotten, having not been part of the castle site since the late 18th century, when it became the site of the General Hospital. The archaeology of the site, which was investigated by University of Leicester Archaeological Services during the site’s redevelopment after the hospital’s closure, was considerable. Among the remains investigated were substantial curtain walls of the Northern Bailey, as well as defensive ditches or moats. The partially disarticulated remains of at least six individuals were recovered, though more than half the bones had been disturbed by a Victorian gas pipe.

Although some of the skeletons were contemporary with the hospital, and were thought to have been used as a reference collection, some of the individuals were interpreted as being of medieval date. The lower half of the skeleton of an adult male was found in the fill of one of the large medieval ditches, and the presence of 12th to 13th century pottery within the fills of this ditch may point to the skeleton belonging to the 13th century. Of particular interest, and intrigue, were remains discovered in 1781 during the digging of foundations for the General Hospital. A mound, described by Thoroton as being of artificial construction and dating to the Civil War, was levelled as part of the works for the hospital and during these works some important discoveries were made.

Fortunately, contemporary accounts exist and these describe how ‘several’ human skeletons were found at different depths. The remains included several skulls, one of which was thought to have marks consistent with a bullet wound. A dagger and two swords, one of which was plated with silver, were also found. The dagger was thought to have been a Scotch Dirk ‘such as are worn by the Highlanders’. A token bearing the date 1669 was, according to Robert Throsby (writing in the 1790s), also found. In addition to the General Hospital, during the 19th century the Northern Bailey became the site of a small number of other buildings including an educational establishment named Standard Hill Academy, a three-storey building with an observatory. It was during the construction of this building that a ‘many relics of the time of Charles the First’ were found, with ten skeletons also uncovered. The skeletons were thought to be male and each, it was reported, had their skulls adjacent to their bodies. A local dentist drew all the teeth but other than a short description written in August 1842 to commemorate the bicentennial of the Raising of the Standard, no records can be found.

The Northern Bailey remains all appear to have suffered violent deaths and it would appear were, at least in some cases, the victims of execution.

Scott Lomax, City Archaeologist

< Previous