Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Incitement to Insurrection? An Unexpected Historical Parallel

By Richard A. Gaunt

Anyone watching events on Wednesday 6 January 2021, when a group of supporters of President Trump stormed (and temporarily took control of) the Capitol building in Washington DC, may have comforted themselves with the thought that nothing of that nature could ever happen in this country - at least not since the exposure of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. The actions of the assembled crowd, troubling enough in themselves, were magnified by the impression -currently the subject of an impeachment trial by the United States Senate - that Trump had incited an insurrection, by intimidating elected lawmakers against ratifying the election of President Joe Biden.

An intriguing historical parallel arises from events in British political history during the spring of 1829. At the time, the passage of Catholic Emancipation - the right for Catholics to be elected as MPs - was dominating public affairs. The issue of granting political rights to Catholics touched a raw nerve which went back to the Reformation and the subsequent history of hostility between Protestants and Catholics. The opponents of the Catholic Relief Bill, the legislation enabling Catholic Emancipation, which was introduced to parliament in February 1829, rallied themselves in a range of ways to oppose the government measure. Brunswick Clubs, named after the British ruling house (the Hanoverians) were formed - although not in Nottinghamshire - openair public meetings were convened (addressed by pro- and anti-Catholic speakers), petitions were circulated for signature and subsequent presentation to both houses of parliament, and parliamentarians who had strongly-held convictions on the issue, were unrelenting in their opposition to the ‘act of betrayal’ entailed in granting Emancipation.

The 4th Duke of Newcastle, of Clumber Park, was a noted ultra-Protestant opponent of Emancipation and was particularly incensed by the fact that it was legislated for by a Tory government headed by the Duke of Wellington. Wellington had decided to introduce Emancipation after the Irish Catholic leader Daniel O’Connell was elected as MP for County Clare in July 1828. Faced with this direct legal challenge, Wellington reached the conclusion that, if Emancipation was not speedily granted, Civil War in Ireland might ensue.

Protestant opponents realised that one of their best hopes of resisting Emancipation was in making a personal appeal to King George IV, whose coronation oath had always been a barrier against introducing the measure. The King, ensconced with his favourites at Windsor (notably his mistress Lady Conyngham), had only reluctantly assented to a Catholic Relief Bill being debated in parliament, and the Protestants directed their attention in his direction. In the middle of February 1829, Newcastle was approached by the Secretary of the London and Westminster Protestant Club to present their petition (estimated at 100,000 strong) to the King at Windsor. The petition was to be delivered to Newcastle at Windsor by a large procession of coaches, and he would then present it to the King. In his diary, Newcastle described the scheme as ‘beyond all precedent but also of such prodigious magnitude that I am sure that no Minister can stand against it - The whole machinery is excellent’. Somewhat portentously, Newcastle observed, ‘this will do & we shall now see who shall be master - & whether we shall preserve our religion & our Laws’. Nothing more was heard of this scheme until Newcastle’s tart observation on 30 March that he had received ‘an odd letter’ from Wellington which Newcastle had answered ‘in his own way, which he will not admire - He wishes to lord it over Every one, he shall not do so with me’.

What had happened in the interim? Newcastle told Wellington that he had only seen the petition for the first time the preceding evening: ‘it was not what I Entirely approved of, but being in circulation [,] it was impossible to Suppress it’. Newcastle noted that the petitioners wished: to mark their respect [my italics] by attending their Petition in carriages to Windsor, where I was to have received it from them & to have laid it before the King - It was, however, Subsequently understood that this mode of Shewing their respect [my italics] on Such an occasion would not be agreeable to the King, & the Scheme was, in consequence abandoned.

It was an established privilege for peers of the realm to request a personal audience of the Crown. This was a device which Newcastle had previously used for political purposes. Wellington suspected that this was being used as cover for an attempt to stiffen the King’s resolve against his ministers and against Emancipation.

Having gone to Windsor to pre-empt the scheme, Wellington learned that the King had not given explicit permission for the presentation of the petition. The Duke proceeded to launch a shrewd counter-assault. According to Ellenborough: [Wellington] impressed upon the King the danger of the Precedent; & Showed the object was to collect a Mob to overawe Lady Conyngham and Persons residing under his Protection. He showed the King the Act of Charles II limiting the number of Persons who might present a Petition. Under the Act against Tumultuous Petitions of 1661, any petitions with more than twenty signatories had to have the consent of three Justices of the Peace to be legal, and only ten people could appear to present them. Having adroitly raised the prospect of a threat to the safety of the King’s mistress, Wellington secured royal approval to dissuade Newcastle against proceeding with the plan and instructed him to send the petition by way of the Home Secretary, Robert Peel. Wellington left open the possibility of a personal audience between Newcastle and the King. Newcastle had - from misjudgement or from ignorance - found himself drawn into the centre of a potentially incendiary situation. For Wellington, it raised serious constitutional consequences. Wellington told the King that it was a dangerous precedent to allow peers to present petitions at audiences because ‘if they Gave answers in the King’s name they became responsible for these answers, & in fact usurped the functions of the Secretary of State’.

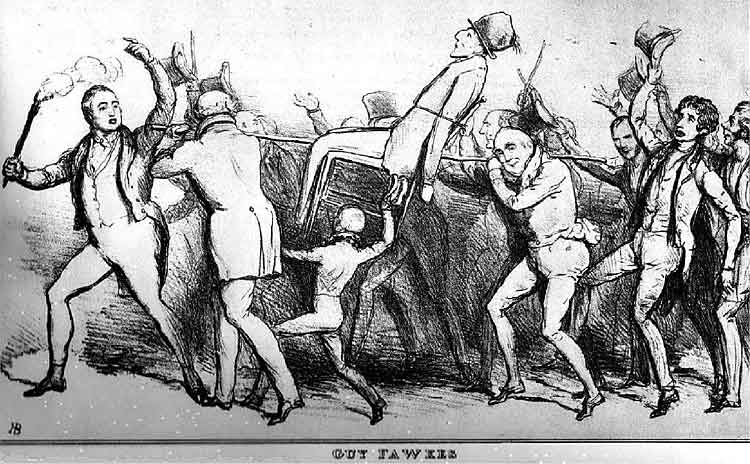

Satirical cartoon by ‘H.B.’ (John Doyle) showing a group of Protestant opponents of Emancipation carrying Wellington, dressed as Guy Fawkes, to a ritual burning. Newcastle is the figure on the far right . (Author Collection).

Events in Washington DC during January 2021 remind us that the proper functioning of government depends upon the careful negotiation between authority and power.

The potential for incitement and insurrection raised by Newcastle’s presentation of the London and Westminster Protestant Club petition, during March 1829, reminds us that this negotiation continues to be a central part of our own history too.

For more on Catholic Emancipation, see Richard’s discussion with Lady Antonia Fraser at: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/exhibitions/online/georgians/lunchtime-talks.aspx

< Previous