Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Waterloo: the Cossall Monument

Shaw and French Cuirassiers at Waterloo, (from Knolly's 'Shaw the Life Guardsman').

2015 is the 200th anniversary of the battle of Waterloo which was fought on Sunday, 18 June 1815. In this article COLIN PENDLETON explores the connection that Nottinghamshire has with the battle through the story of soldiers named on a memorial in the churchyard of St. Catherine's church at Cossall. It is a fascinating story of brave deeds and posthumous fame.

Surveying the slaughter of Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington commented that 'there is nought so melancholy as a battle lost as a battle won'. As we celebrate the bicentennial of Waterloo on June 18th 2015, this famous quote is sure to be revisited. What may get less attention, but which is perhaps of more interest to Nottinghamshire historians, is the macabre story of local legend Corporal John Shaw, his brave deeds... and the strange desecration of his grave at Waterloo.

Shaw was born on a farm between Cossall and Wollaton in 1789. His baptism is recorded as January 3rd 1790 and Shaw disappears into the mists of history until Truman's The History of Ilkeston suggests that his schooling may have been carried out at a Mr Newton's school on Trowell Moor. Whatever Shaw learned, it would be unlikely to have been extensive and at the age of 13, according to Truman, he was apprenticed to a joiner and wheelwright, later becoming a carpenter on Lord Middleton's estate at Wollaton Hall.

Contemporary accounts suggest that Shaw's life would have been a hard one. Trades in the area all reflected the manual labouring that was the main source of income for the working class at the time: mining, farm labouring and framework knitting. It is suggested in Major Knollys' book Shaw The Life of a Guardsman, published in 1876, that he joined the 2nd Life Guards at Goose Fair in 1807, aged 18.

According to Bailey's Annals of Nottinghamshire, Shaw was a big man and extremely strong. When his skull was later on display it could be seen to have two missing teeth, suggesting that he was both distinctive and singularly fearsome. After enlisting in the Life Guards he continued to improve his boxing skills, becoming extremely popular, and it is not hard to imagine what a daunting opponent he must have been. Knollys suggests that he was one of the regiment's best prizefighters and would have been popular at all levels of society, in the words of the Nottingham Date Book for 1815 'He was a tremendous pugilist, fought several times in the ring and was never beaten'.

It was, however, Shaw's exploits during the battle of Waterloo that were destined to give him posthumous fame. John Keegan's book The Face of the Battle provides a reference to Shaw in a letter from Cornet Gape of the Greys to his mother following the battle: 'The men were only too impetuous, nothing could stop them, they all separated, each man fought by himself; and the famous Corporal Shaw of the Life Guards certainly sought out opponents - he was very conspicuous dealing deadly blows all around him.'

Exactly how Shaw fell is unclear. Alessandro Barbero's book The Battle states that 'One of the French Cuirassiers withdrew from the fight and shot Shaw from his horse'. Knollys' account states that Shaw became isolated and surrounded by French Cuirassiers and eventually cut down. Bailey's Annals of Nottinghamshire dated 1815, and a similar account in The Nottingham Date Book, state that: 'Shaw suffered many small wounds throughout the battle and he eventually died from exhaustion and loss of blood'. It appears that he was able to make his way to La Haye Sainte farmhouse and was still alive when found near a wall and died sometime during the night. Sergeant Major Cotton of the Seventh Hussars was present at Shaw's burial at La Haye Sainte the day after Waterloo.

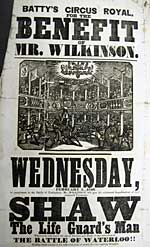

Batty's Circus Royal Poster (Reproduced by kind permission of the Nottinghamshire Archives; ref: DD/Ml/196.

A measure of the interest and acclaim that Shaw was subject to can be seen by a poster which is in the Nottinghamshire Archives. On Wednesday, February 5,1840, twenty five years after the last musket had been fired, and in the excitable description on the poster, Hatty's Circus Royal held a performance by a Mr Wilkinson giving his: 'celebrated impersonation of Shaw, The Life Guard's Man. Wherein he will depict the manly Prowess and Death of that individual at the Battle of Waterloo!! Dealing death around to his numerous foes, in nearly his own expiring struggles.' That Shaw should be remembered in Victorian theatricals two and a half decades after he fell is a remarkable testament to his hold over the popular imagination. This was as close to a popular hero as we are ever likely to see.

Where the story becomes interesting, not to say bizarre, is on the matter of what happened to his skull. According to the fourth edition of Knollys' book published in 1885, edited by J. Potter Briscoe, who was the Public Librarian of Nottingham, a human skull was on display at The Royal United Services Institution, Whitehall Yard Museum, London, suggesting that, not only had the grave been opened, but Shaw's skull had been removed.

It had possibly been on display for 60 years. The skull had been recovered from the grave of Shaw, near the wall of La Haye Sainte and had large and very prominent teeth, two of which were missing, one of Shaw's most distinguishing features. The late Sergeant Major Cotton, who was a guide to the battlefield of Waterloo for many years, was also present when the skull was exhumed. The label read 'Skull of Shaw, the famed Life Guardsman who fell at Waterloo, procured by the Late Admiral Ryder'. What 'procured' means in this context is unclear. Did the Admiral have the grave opened with the intent to remove Shaw's skull? Did he mean that it be displayed publicly? The answers may never be known. As an active member of the Church of England's impressively named Purity Society, however, it may be safe to assume that the motive was devout patriotism, rather than any inherent ghoulishness.

A collection of documents in the Nottinghamshire Archives appears to support the information regarding Shaw's skull. A letter to the Reverend H. C. Russell, The Rectory, Wollaton, Nottingham dated May 26th 1898 from General R. Maltby states:

'I am writing privately to ask you if it would be possible to place the skull of John Shaw the Life Guards Man who was killed at Waterloo under, or adjacent to the Memorial to him, and Tom Wheatley of the 23rd Light Dragoons created in Cossall Church yard. The reason I am asking for information is, that John Shaw's skull has been in our museum for the last 11 years in our old quarters, the Public were not admitted, but now we have come over to the Banqueting House Whitehall the Council don't think it very seemly to have on view the skull of a British Soldier & would like to find some suitable resting place. It would be very kind if you would let me have your views on the matter, I think it is essential that whatever is done should be done quite privately.'

There does not appear to be any correspondence from the Reverend Russell other than a note dated March 19th 1918 stating that: 'This skull was buried by me June 21st 1898 in Wollaton church close to the pillar near the font - in the presence of W. Harwood and Alfred Meats.' This brings to a close a singularly grisly story. What is not resolved, however, is the unusual story of the memorial.

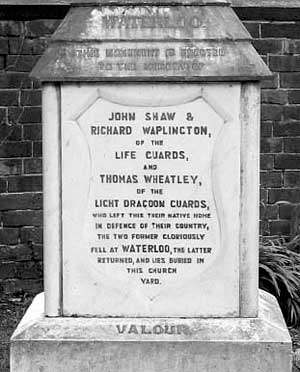

The Waterloo Monument in the churchyard of Cossall Church (photographs by Colin Pendleton).

It could be that W. Jackson's design and sculpting of the Waterloo memorial in the churchyard of St Catherine, Cossall was a result of Shaw's posthumous legend, but the most striking aspect of the memorial is its stark whiteness in the muted tones of a country churchyard. A white marble obelisk with a wreath of ivy leaves near the summit and a carefully sculpted helmet, crossed swords and breast plate of a Life Guardsman at its base, it seems designed to remember the twenty or so men on the Great War memorial that flanks it, rather than the three men who would find their names there. The inscription, with characteristically florid Victorian sentimentality and an eye for martial glory, reads:

'Waterloo. This monument is erected to the memory of John Shaw and Richard Waplington, of the Life Guards, and Thomas Wheatley, of the Light Dragoon Guards, who left this their native home in defence of their country, The two former gloriously fell at Waterloo, The latter returned, and lies buried in this churchyard. Valour.'

Of the two other men, Richard Waplington, also fell during the battle, and Thomas Wheatley, unusually for a war memorial, actually survived and returned home to Cossall.

According to Truman, Thomas Wheatley was born in Cossall Marsh in 1795 and attended school in Cossall. He became an apprenticed stocking weaver at the age of nine. He enlisted in the 23rd Light Dragoon Guards and fought at Genappe on June 17th and Waterloo on June 18th. He survived and returned home to Cossall and worked in the blacksmith's forge at the Babbington Colliery Company. He was also part of the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry Cavalry. Wheatley ended his days in Cossall and the Waterloo memorial may have been placed above his grave.

Little is known, however, of Richard Waplington other than what can be found in Truman. The book suggests that he was born in Cossall in 1787 and may have attended school on Trowell Moor with John Shaw. At the age of 12 he seems to have been working in a local colliery and much of the rest is supposition. He enlisted in the Life Guards with Shaw in 1807 and as part of the 2nd Life Guards Waplington may have been involved and fell in the same action. It is mentioned in Knollys' that during a review of the 2nd Life Guards by King George III and the Duke of Wellington, Waplington was called from the ranks. The King reputedly asked Waplington which county he came from. Waplington replied 'from Cossall, Nottinghamshire your majesty'. The King remarked to the Duke of Wellington 'He is a very fine soldier, but he comes from a riotous county'.

In the quiet seclusion of Cossall churchyard, it is impossible not to look at the memorial, contemplate the names on it and consider a quote from Alessandro Barbero's book, The Battle, in which he describes a sabre fight between the Life Guards and French Cuirassiers as 'brief and exceedingly violent'.

What is more certain is the date and time the obelisk was unveiled. On June 3rd 1875 The Ilkeston Pioneer reported that a committee had been formed to raise funds for a tribute, which attracted contributions from HRH The Duke of Cambridge and various dignitaries of the district, including Earl Cowper, Earl Manvers and Lord Middleton, as well as Sir Henry Wilmot, a distinguished soldier who had won the VC during the Indian Mutiny, local gentleman Lancelot Rolleston JP, who was also a Captain in the South Nottinghamshire Yeomanry and High Sheriff of the County. The Nottingham Journal of June 23rd 1877 provided a comprehensive account of the unveiling ceremony on Monday 18th June at 4.30 pm, 62 years after the battle had taken place. Lancelot Rolleston reportedly led the proceedings, regaling the crowd with a patriotic description of Shaw's life and deeds. What the families of Richard Waplington and Thomas Wheatley might have thought, if they were present, is not recorded.

A representation of Shaw in the Life Guards Museum in London (photo Colin Pendleton).

There is, possibly, a strange postscript to the story of Shaw's skull. While it was certainly in the possession of Admiral Ryder, it may be that another, more famous name was involved in the exhumation. One of the guides at Waterloo claimed that 'an eminent confidential tourist' visited the grave of Shaw at La Haye Sainte, and the guide informed the tourist that he saw Shaw's body and was struck by the extraordinary muscular development and appearance of great strength. Alessandro Barbero suggests in his book that it was actually poet and novelist Sir Walter Scott who had Shaw's body transported to England, as he was known as one of the Corporal's most vocal admirers. This is tempting to believe and certainly a more romantic notion than Shaw being exhumed by a member of a church purity society. Again, the exact identity of the person, whether admiral or poet, remains unknown.

Scott certainly had a plaster cast made of Shaw's skull, which is presently on display in the Horse Guards Museum in London. Scott revisited Shaw's story many times in his personal letters as well as his published works. What is certain is that he immortalised Shaw in a poem that, as we approach the two hundred year anniversary of the battle and consider this strange tale, must stand as his epitaph:

Nor 'mongst her humbler sons shall

Shaw e'er die,

Immortal deeds defy mortality.

Bibliography

Nottinghamshire Archives Office:

Correspondence & Notes PR 7753 /1-7

Battys Circus Royal Poster DD/MI/ 196

The Nottingham Review 30 June 1815

Ilkeston Pioneer 3 June 1875

The Nottingham Journal 23 June 1877

Nottingham Evening Post & News 27 May 1965

Wright's Directory of Nottingham (1879), p.349

Bailey Thomas, Annals of Nottinghamshire, History of the County of Nottingham Including The Borough Vol. IV (1815) pp.276-7

Barbero, Alessandra The Battle, A New History of The Battle of Waterloo (2005) p.147, p.316

Doubleday W.E., Nottinghamshire Villages, The Last 600 Years of Cossall's History, (1945), pp.8

Howarth David, Waterloo-A Near Run

Kegan John, The Face of Battle (1976), p.145, p.181

Knollys Major, Deeds of Daring Library, Shaw The Life Guardsman:

An Exciting Narrative (1876)

Knollys Major, Deeds of Daring Library, Shaw The Life Guardsman:

An Exciting Narrative, Revised & Edited by J. Potter Briscoe. (1885)

Truman Edwin, The History of Ilkeston Together with Shipley, Kirk Hallam, West Hallam, Dale Abbey & Cossall (1880), pp.92-8

The Date-Book of Remarkable & Memorable Events Connected with Nottingham & Its Neighbourhood 1750 -1879, (1815) pp.301-2, (1877) P-587

Acknowledgements

Battys Circus Royal poster DD/M1/196 reproduced by kind permission of The Nottinghamshire Archives

Grateful thanks to The Household Cavalry Museum, London for information provided.

< Previous