Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

William and Mary Howitt: A Literary Marriage

by Rowena Edlin-White

This article first appeared in The Southwell Folio, No. 10, July/August 2011 and is reproduced here by kind permission of the author, Rowena Edlin-White who has an fascinating talk on William & Mary Howitt available to Societies. Rowena may be contacted on ro@edlin-white.net for further details.

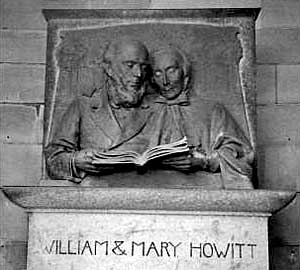

In the portico of Nottingham Castle, in company with other local literary worthies, you cannot fail to notice the handsome double bust of William and Mary Howitt. ‘Who were they?’ you might wonder, before passing on.

The Howitts are entrenched in the literary history of Nottingham, an intriguing couple with a phenomenal output of some 170 books between them from the time of their marriage in 1821, not to mention political pamphlets, periodicals and numerous translations.

They were both brought up as Friends - Mary Botham in Uttoxeter as a ‘Plain Quaker’, a strict form; William in a more liberal strain, in Heanor. As a couple they gradually moved away from their Quaker upbringing, exploring mysticism, Catholicism and even spiritualism, but for a long time continued to use the characteristic ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ and refer to the day of the week as ‘First Day’, ‘Second Day’ and so on.

William was steered towards architecture as a career, beginning with a four-year apprenticeship to a carpenter in Mansfield, a subject of little interest to him, except for the proximity of Sherwood Forest which fired his poetical imagination. Here he ceremoniously tore up and scattered his indentures to the wind. After several years on the family farm, he settled for a career as a pharmacist, practising briefly in Hanley.

Mary and William were both keen walkers and admirers of landscape in the Wordsworthian fashion and they enjoyed a late honeymoon in 1822, travelling some 500 miles on foot around Scotland and the Lake District. They wrote up their experiences for the Staffordshire Mercury. in August the same year, they settled in Nottingham. The following spring, Mary was thrilled to see a famous local attraction – acres of purple crocus flowers in the Meadows – and wrote her poem Wild Crocus in Nottingham Meadows.

One of the first things they did was to join the Nottingham Subscription Library which had only recently moved to Bromley House on Angel Row. They remained members until 1836, enjoying the company of like-minded people. Their arrival coincided with their first collaborative book, The Forest Minstrels and Other Poems, published in 1823, the title poem inspired by William’s ramblings in Sherwood forest. Of course, they presented a signed copy to the Library where it may still be perused, along with many of their other publications.

From their home on South Parade, the couple were soon involved in the local literary scene, writing more poems than prescriptions, and the chemist’s shop on Parliament Street was taken over by William’s brother, no mean poet himself.

When Byron died in 1824, his body was brought back to England for burial. On the 18 July, en route to his funeral, it rested overnight in a public house behind the Exchange and the Howitts went to do homage. Mary wrote, ‘We laid our hands upon the coffin. It was a moment of enthusiastic feeling to me ...’. William followed the procession to Hucknall and his poem A Poet’s Thoughts was written immediately afterwards. The Howitts duly acknowledged Byron’s controversial life, but took the view that he was a poetic genius and deserved due respect as such.

The proliferation of periodicals and annuals at this period gave the Howitts many opportunities to

exercise their literary muscle. Mary, in particular, found her feet writing moralistic stories and poems for the young – her famous poem, The Spider and the Fly comes from this period. William, meanwhile, wrote a number of books based on his travels, e.g. The Homes and Haunts of the British Poets and Visits to Remarkable Places, which are still valuable as early travel books. They both began to make a reputation for themselves, whilst bringing up a large family (Mary gave birth to eleven children which survived but several more were still-born).

In May 1831 they had a surprise visit from Mrs. Wordsworth and her daughter Dora, the poet’s wife being taken ill whilst travelling home, and for the first time they met the great man. ‘He is a kind man, full of strong feeling and sound judgement ... My greatest delight was, that he seemed so much pleased with William’s conversation,’ wrote Mary. Actually, William scandalised the Wordsworths with his opinion that the Church of England should be devolved forthwith, but maybe they were too polite to argue!

Embroiled in politics

That same year Nottingham was inflamed (literally) by the Reform Riots, and the Howitts were firmly on the side of the poor, anticipating an English revolution. They stood on the roof of their house in South Parade and witnessed the burning of the Castle.

William was getting more embroiled in local politics, and was elected ‘against his will’ as a Radical alderman in 1835. He began to find his council duties an impediment to his writing and they began to think of leaving Nottingham for somewhere quieter. In August 1836 they moved to Esher in Surrey – though not before undertaking a three-month tour of the north of England and Scotland, once again walking ‘hundreds of miles’.

In Esher they became friends with Byron’s widow and her daughter the Countess of Lovelace, getting involved with them in educational reform and opening village schools, while Mary educated her six surviving children at home. They were also involved in the Anti-Slavery movement during this period, William’s brother Godfrey and family emigrated to Australia, and Mary wrote that she was ‘thankful that we have no emigrating mania upon us ... we will abide by old England’. But this didn’t last and by 1840 they had decided to move to Germany for a few years for their children’s education.

Travels and translations

Both Howitts were natural linguists, and whilst living in Heidelburg, Mary learnt Danish in order to translate the works of Hans Christian Anderson, who became a rather difficult acquaintance, labouring as he did under the misapprehension that the Howitts had made a fortune out of his books. The truth was, they barely covered the cost of printing. Mary also learnt Swedish and translated

18 novels of Frederika Bremer, who was to become a close family friend. For this, Mary was awarded a useful pension of £100 a year from the Literary Academy of Stockholm. Both Anderson and Bremer were introduced to the British public through Mary’s talents.

Back in London during the 1850s, both Howitts contributed anonymously to Dickens’ Household Words. They began a similar enterprise of their own – Howitt’s Journal – but it was a financial flop and only ran to two volumes. On the whole, Mary’s series of children’s stories - often set in the Uttoxeter of her childhood – proved most remunerative. Their daughter Annie married Alaric Alfred Watts, son of the painter, and through him the family got to know the pre-Raphaelite painters and their set: Millais, the Rosettis, Holman Hunt and William Morris. They lived in an artistic, even Bohemian, milieu – a long way from their strict Quaker origins.

In 1851 William went to Australia with their sons, Alfred and Charlton, to join Godfrey in the gold fields. They were away for two years and sometimes Mary and the rest of the family – now living in Highgate – heard nothing for months, or only through the newspapers. She found this period particularly trying but, encouraged by a neighbour, Angela Burdett-Coutts, threw herself into the Anti-Slavery campaign, meeting Harriet Beecher Stowe during her tour of Britain. She also joined Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Elizabeth Gaskell in raising a petition for the Married Women’s Property Act. If nothing else, their Quaker origins had given the Howitts a strong belief in the equality of all people, irrespective of race or gender.

The family still hankered for a permanent home abroad, and in April 1879 William, Mary and their youngest daughter, Margaret, left for a year in Switzerland and Italy. Mary was now 71 and William 78, but they walked and climbed mountains and thoroughly enjoyed themselves. By 1874 they had settled into a summer home at Meran in the Tyrol, spending their winters in Rome, where they joined a lively, artistic, ex-pat community.

William died in Rome on 3 March 1879 and was buried in ‘that most beautiful of all burial places, the Protestant cemetery’. After his death Mary and Margaret built themselves a home of their own at Meran on the proceeds of Mary’s Swedish pension. Mary had become more and more interested in Catholicism and in May 1882 she was baptised into the Roman Catholic church. She died on 30 January 1888, ready to join her beloved husband. But here was a problem! Now she was a Catholic, Mary was not, strictly speaking, allowed to be buried with Protestants! Special permission had to be obtained from the Vatican before she could join William and lie in the good company of Shelley and Keats and all the other artists and writers who had happened to expire in the ‘eternal city’.

< Previous