Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

The Midland Counties Railway, 1839-1844

Some Notes at the 175th Anniversary of Nottingham’s First Steam Railway

By Kerry Donlan

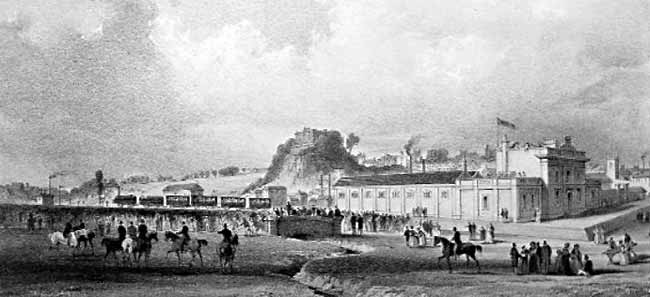

The opening of the Midland Counties Railway at Carrington Street Station, Nottingham on 4 June 1839.

The study of history is closer to being a process of research and re-evaluation, of offering a contribution to a developing insight into the topic studied assisting others to make further contributions, rather than an objective achieved, a final sacrosanct definitive conclusion.

The steam railway, from 1804, did not create the fundamental economic, social and political changes evident in Britain at this time, but was itself created by, and accelerated, these changes.

By the mid 19th century, Britain had become the first industrialised, urban majority society in history. Christine Legarde, manager of the International Monetary Fund, stated (2014) that by 2030, 60% of the world’s population will live in big towns. Such a transformation is only possible with the mobilising of capital, greatly increased manufacturing and agricultural effciency, responsive government ensuring the provision of clean water, hygiene, shelter and education. The effective transport of food, fuel, raw materials and manufactures is essential to this process.

Origins of the Midland Counties Railway

Coal was the main fuel for manufacturing and for domestic use, it was heavy and a high percentage of its sale price was consumed in road transport costs, restricting both consumption and profts. Water-borne coal traffc was more effcient but limited by accessibility. The canal network reduced transport costs and helped increase demand. The opening of the Leicester and Swannington steam railway in 1832 directly threatened the profts of the Derbyshire coal owners’ traffc to Leicester. Unless a more efficient transport method was brought into use the Derbyshire coal owners would be priced out of the Leicester and other markets. Only a steam powered railway could protect their investments and proftability.

The Inauguration of the Midland Counties Railway

Local and Personal, 6 and 7 Gul IV, cap lxxviii, 21 June 1836. An Act for making a railway, with branches, commencing at the London and Birmingham Railway in the parish of Rugby in the County of Warwick, to communicate with the towns of Leicester, Nottingham and Derby to be called ‘The Midland Counties Railway’.

The Midland Counties Railway was:

| 21 June 1836 | Inaugurated |

| 30 May 1839 | Operated |

| 10 May 1844 | Amalgamated with the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway and the North Midland Railway to form the Midland Railway (1844-1922) |

| The railway linked: | Nottingham |

| Derby | |

| Loughborough | |

| Leicester | |

| Rugby |

Although the life of the railway was brief, it was evidence of rapidly accelerating modernity and drew Nottingham more closely into this process.

Midland Counties Byelaws, Orders and Regulations

The Midland Counties railway stone coat of arms from the top of the 1839 station on Carrington Street. This is now preserved at the Wollaton Hall Industrial Museum. The arms are those of the counties through which the railway ran; Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Warwickshire,

Parliament empowered the railways to make such Byelaws as deemed needed for the operation of the railway.

iv. No dogs allowed in carriages, conveyed separately and charged for.

v. Smoking prohibited in carriages and stations, warned, fined, removed from train and premises. In 1868 carriages for smoking were required by legislation.

vi. Intoxicated, nuisance, warned, removed from train at next station.

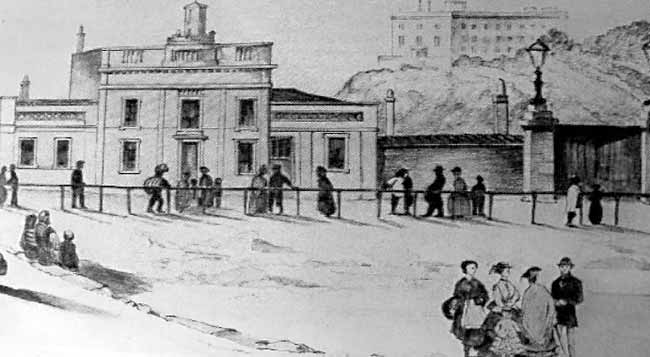

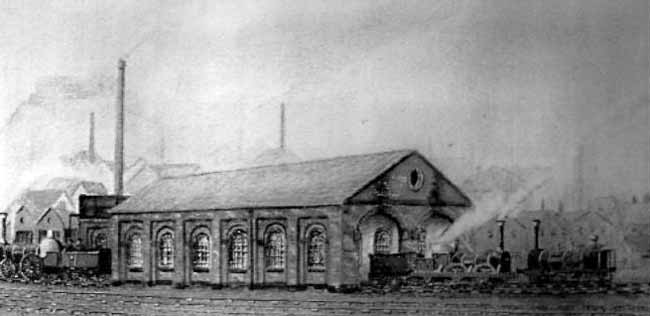

Contemporary illustrative evidence of the Midland Counties is confined to paintings, engravings and sketches. A number of these feature scenes from Nottingham. Apart from showing the railway these scenes are valuable primary evidence of the physical context in which the railway existed. The railway did not involve the mass scale demolition of buildings in Nottingham as it was inaugurated, built, operated and amalgamated before The Meadows Enclosure Act of 1845.

In any meaningful sense, the railway pre-dates photography. Fox-Talbot published his research into photography in 1839, the year the railway opened between Nottingham and Derby. Had he been able to complete his research earlier, perhaps some photographic record of the Midland Counties could have been compiled before it disappeared in the 1844 amalgamation.

1843. The Midland Counties Railway Station on Carrington Street, Nottingham. Before the road bridge across the canal was built in 1841, entrance to the station was from Wilford Road. Only the two gate posts of the station now remain.

Nottingham Market Day Road Traffic Survey, Saturday 11 September 1819, 5am to 5 pm by William Stretton A Private Survey

Nottingham had an intensive level of road traffc, from local and more distant locations. The west of the town recorded the highest level of the four ‘stations’ in the survey.

| Total people | 7,376 | 51% |

| Horseback riders | 297 | 31% |

| Carriers | 46 | 30% |

| Pack Horses | 19 | 8% |

| Total number of vehicles | 294 | 30% |

Pigott’s Directory of 1819 records that Nottingham had seven inns and 177 public houses with accommodation for nearly 1,000 wheeled vehicles and 2,500 horses. Nottingham’s stage coach services operated from the 1750s to the 1850s.

White’s 1832 Directory lists 35 stage coaches, but only one in 1853, the Sheffeld Royal Mail. The entry of the railway from the West was, in part, influenced by this existing level of trade.

The steam railway in Nottingham offered hotels a greater opportunity to seek business. Adverts were placed in guides, directories and the press, emphasising the convenient location of the hotel to the station and the (horse drawn) bus service from the hotel to the railway station. This assisted the commercial and private traveller, creating employment and profts.

Nottingham - Railways and Canals

The canal network made a fundamental impact on the development of the urban industrial economy, in particular the large inland industrial centres such as the West Midlands and the North West. Canals were effective in transporting heavy cargo including coal, reducing the percentage of the selling price consumed by transport costs, enabling the extension of the market for these goods.

The canals were a stronger example of laissez-faire economics than the steam railway. The canal companies decided the gauge and tolls, but the steam railways were clearly the future. The problems of operating canal traffc were insurmountable when confronted by the steam railways. Traffc moved at walking pace and could not be speeded up because of wash against the banks. There was, on average, one lock every 13/4 miles of canal routes.

Many canal companies’ profts collapsed, encouraging shareholders to co-operate in selling their canals to railway companies. The railways had a motive in taking over canals, to eliminate competition and acquire possible routes. The Great Northern Railway took over both the Nottingham and Grantham canals. In the three years following the formation of the Midland Railway, 1845-1847, 948 miles of canals, almost 25% of the network, were taken into railway owneship.

Coal was the main fuel of the rapidly expanding manufacturing trading urban society of 19th century Britain. Canals and navigations had greatly infuenced these trends, but the steam railway provided a much more efficient and extensive transport network, reducing the cost of coal to the consumer, increasing demand and drawing more investment into the coal industry.

Nottingham beneftted from the more effective provision of coal, assisting economic development but also would suffer from increased coal smoke and industrial pollution. At the time of the Midland Counties Railway 1839-44, Nottingham was, in many areas, an overcrowded and insanitary town.

In the only complete calendar years of the Midland Counties, 1840-1843, in Byron Ward on average, 44.5% of children died before their fourth birthday. The railway did not create this situation, but with the clean air acts far into the future, the increased level of air pollution was not a safeguard to good health.

Investment on Locomotives and Rolling Stock

The company directors must calculate the best return on the investment of limited resources, which areas of traffic development would be most sustainable or grow? Which the most profitable? The railway was a carrier, a provider of a service, it had no control as to who would patronise its service, an economic downturn could result in fewer passengers and a fall in freight conveyed, resulting in a fall in revenue. Nottingham’s economic fortunes would, in turn, impact on the railway.

By November 1842, the company had possessed 47 steam locomotives of varying quality, provided by:

| The Butterley Company | 2 |

| Jones | 5 |

| Nasmythe and Co. | 7 |

| Fairbaine | 2 |

| Stark and Futton | 3 |

| Bury | 19 |

| Hick and Sons | 9 |

The Midland Counties pre-dates many railway companies building their own locomotives and rolling stock.

20 November 1842 - Rolling Stock - evidence of achieved and anticipated traffic:

| First class carriages, including 3 coupees | 35 |

| Second Class carriages, open | 39 |

| Third Class carriages | 13 |

| Horse Boxes | 19 |

| Parcel Vans | 4 |

| Goods Wagons | 95 |

| Timber Trucks | 7 |

| Coke Wagons | 16 |

| Second Class carriages, closed | 13 |

| Composite carriages | 8 |

| Carriage Trucks | 25 |

| Mail Vans | 3 |

| Luggage Breaks | 4 |

| Cattle Wagons | 18 |

| Coal Wagons | 80 |

| Ballast Wagons | 24 |

| Iron Coal Boxes, or Loose Bodies where two go on one wagon | 80 |

| (The Coal Boxes and Loose Bodies indicates an early example of efficiency, but would need to return these for re-loading). | |

The number of passenger carriages providing better than Third Class accommodation far exceeded the Third Class provision (95 - 13). This reflected the relatively expensive ticket price when set against the modest incomes of many potential customers. The balance of passenger provision is also evidence of the prevailing social class origins of many travellers. 25 carriage trucks and 18 horse boxes were provided for those bringing their road coaches with them to facilitate road travel to the station and to their fnal destination.

Nottingham’s patronage of the railway services would be reflected in the differing levels of passenger provision. The 1844 Railways Act, with its ‘1d a mile’ clause did not affect the Midland Counties Railway, post-dating it by 3 months.

Nottingham and the Carrying of Mail by Steam Railway - the Act of 1838

The Post Offce was a state monopoly, with powers to obtain the most efficient, secure and impartial provision of the mail service. The duty of the State was, (according to Gladstone), to remove obstacles to self-improvement. Horse-drawn mail coaches were a slower, less secure, expensive transporter of the mail, compared with the steam railway. Britain was experiencing the rapid growth of the mining, manufacturing, trading, capital raising, agriculture enclosed and urbanised economy and society. Population, literacy and foreign trade were increasing. The growth of the volume of mail rapidly increased before Rowland Hill’s reforms of the postage stamp rates. Nottingham was both a contributor to, and a beneficiary of, these changes. In an age before the telephone and the telegraph, the mail service was increasingly significant.

In 1837 the London and Birmingham Railway and the Grand Junction Railway opened, linking London with the world’s first centre of mass scale mechanised production - Manchester, and with Britain’s second port - Liverpool. In 1839 the Midland Counties Railway, with the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway, linked Nottingham into this new advantageous transport opportunity, joining the London and Birmingham Railway at Hampton. In 1840 the Midland Counties linked Loughborough and Leicester with London at Rugby.

The 1838 Act - ‘An Act to provide for the conveyance of mail by Railways’ - empowered the Postmaster General to:

“That in all cases of railway already made or in progress or to be hereafter made within the U.K., by which passengers or goods shall be conveyed in or upon carriages drawn or impelled by the power of steam, or by any locomotive or stationery engine or animal power or other power whatever ...”

Railways must provide mail transport by:

• Ordinary trains of carriages

• Special trains as need may be

• At such hours or times in the day or night as the Postmaster shall direct

• With guards appointed and employed by the Postmaster

• A whole carriage for mail if required

• In November 1842, the Midland Counties Railway had three mail vans

• When required, a carriage fitted out for mail sorting (the Travelling Post Office [TPO])

• Royal Arms to be painted on mail carriages and engines

• Post Office will pay reasonable remuneration

• Rail company wholly responsible for its servants’ compliance with Post Offce regulations

• Post Office can require a bond deposited by the railway company or a £100 daily fne

The Midland Counties integrated into these improved communications imposed by the State, drew Nottingham more closely into the national and international economy, providing increased opportunities for investments, profits and employment, but also subjected the town to fluctuations in the above that were, in the main, out of Nottingham’s control, for example 1842.

The economic downturn of 1842 impacted on the Mildand Counties Railway. As a carrier, its revenue was directly affected by the level of passenger patronage and goods requiring shipment.

Five railway companies’ shareholders formed committees to investigate, with the company directors, as to how this matter was being dealt with.

Shareholders of the Midland Counties and the North Midland, both constituents of the 1844 amalgamation to form the Midland Railway, formed such committees.

The Inspector General of Railways wrote to the Midland Counties and others, expressing concern at the discussions regarding cutting the wages of their enginemen and the latter leaving the company, impacting on the company’s ability to maintain the service. Other staff reductions raised the questions of public safety.

1839: The Midland Counties Railway Locomotive Depot. The County Archives offce now occupies the approximate site.