Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

When “Rock City” Rolled

As Rock City, the music venue on Lower Talbot Street, Nottingham, has marked the thirty fifth anniversary of its opening – on the 11th of December 1980 – perhaps now is a good time to look at the history of this Victorian building. It is 140 years old this year and the first three quarters of its life saw a few changes.

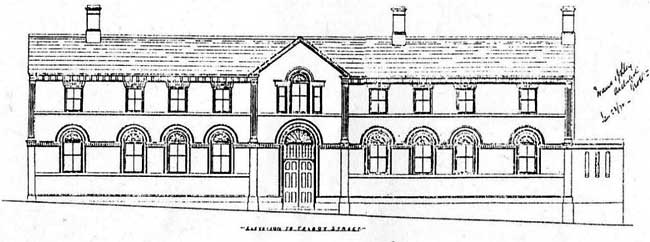

The Talbot Street frontage of the Alexandra Skating Rink. Source: Nottingham Civic Society Newsletter No. 79 (1989), page 15.

This frontage, designed by Evans and Jolley, is stylistically like the completed building, which itself has been much altered, with additional entrances and drains, but is still recognisable.

In December 1875, Edward Baker Cox, the proprietor of the Talbot Hotel [Yates’s], Long Row, Nottingham, opened the Alexandra Skating Rink behind his establishment, with an entrance at 13 Market Street. This rink was for roller skating. Indoor ice skating rinks did appear in 1876, but Nottingham’s old Ice Stadium was not built until 1939, just in time to be used as a munitions dump. Mr Cox may have opened this rink as a stop-gap or thought it too small but, for whatever reason, the next year he converted it into the Palace of Varieties Music Hall and proceeded to open TWO skating rinks on Talbot Street. These were our building, to which he transferred the name, the Alexandra Rink, and the Marble Rink, which was situated just up the hill, only separated from the Alexandra by what became the Stanley Place cul-de-sac. Both buildings were built under the auspices of the Leicester and Nottingham Skating Rink Company (Limited), of which Edward Cox was the managing director, and used the same architects Messrs. Evans and Jolley. The point about this skating rink company is that it held the local concession for Plimpton skates. These skates, patented by the American James Plimpton in 1863, were self-steering, so that as the skater leant to one side the inside wheels moved closer together causing the skater to turn. This was a great improvement and with the adoption of roller bearings and rubber tyres skating became a lot easier and more enjoyable, especially for the fairer sex. The Alexandra opened on the 24th of November 1876 and may have been owned by Mr Cox, which would explain the capital ‘C’s above the first floor windows. Its floor was certainly bigger than its predecessor at 155 x 95 feet against 120 x 45. The skating floor surface was the defining difference between the two Talbot Street rinks. The Alexandra’s skating surface was of asphalt, supplied by the Birmingham Val de Travers company, while the Marble Rink’s floor was marble. The Marble Rink opened on the 12th of February 1877. The floor, 165 x 45 feet, was paved with slabs of white Sicilian marble with the crevices between the slabs filled with the greatest care, so as to be ‘no hindrance to the impetuous course of the skater’. The illumination was by an iron gas pipe perforated with innumerable holes running above the balcony. A lighted wick was fixed in a cradle and then raised to the level of the holes and drawn around the whole building by a man below. I would have liked to have been around when they lit the gas lights, although, on second thoughts, perhaps not. In September 1877 the rink invested in an aquarium and large rockery requiring several tons of the porous limestone tufa. When the aquarium opened it included, amongst its many wonders, two seals. This rink seems always to have been the poor relation of the Alexandra and although it shared attractions it only lasted until 1885. Its fixtures and fittings auction in that May included 600 pairs of the Plimpton skates. The building became a warehouse for Pilkington Glass and remained a warehouse until its demolition around 1990, despite the Nottingham Civic Society’s attempt to save it.

Meanwhile Alexandra Halls, as it was sometimes called, was designed from the start as more than just a skating rink. Kelly’s Directory of 1904 stated that, ‘the hall will seat 2,500 persons, and is used for entertainment etc., and also as a skating rink; adjoining are two smaller halls one 65 x 75 feet, with 700 sittings, and another 33 by 22 feet’. So between skating sessions, as the craze waxed and waned over the years, the halls were used for many other purposes. The most common, naturally, were balls, dances and the ubiquitous whist drives, but there were other, perhaps more surprising events. William Gladstone, the four times Liberal Prime Minister, addressed nearly 10,000 people there on the 27th of September 1877. He was attending the laying of the University College foundation stone, being between premierships. The rink also hosted specialist entertainments, tight rope walkers, gymnasts and the strongwoman Mademoiselle Valerie, whose ‘glorious physique’ was ‘the one theme of conversation throughout the town’. In late 1880 Mr Cox, ‘took back’ the Alexandra Rink from the Rink Company and offered it as a home to the Nottingham Gymnasium. The Gym was looking to relocate from Waterway Street, the Meadows - ‘an unpromising locality’. They were also attracted by the close proximity to the Turkish baths in Stanley Place which ‘offers an inducement of another sort’. The buildings were not only used as a gymnasium as in December 1881 a meeting of the Nottingham Branch of the National Skating Association was held there. This ice skating association had been formed two years earlier to help combat undesirable betting and cheating amongst the sport of Cambridge Fen speed skaters. Nothing changes. In 1882 there was the Poultry, Pidgeon and Rabbit Show, while in 1884 Edward Payton Weston spent two days in the Alexandra, walking fifty miles each day, which equates to something like 650 circuits of the hall. Weston was a notable American ‘pedestrian’ [long distance walker] who was attempting a 5,000 mile walk around Europe. The secret of his success was supposed to be his habit of chewing coca leaves. In 1887, to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, the building’s name was changed to the Victoria Hall.

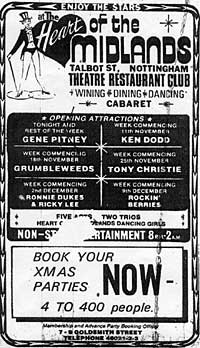

The building now entered what we might call its circus years. In most of the years between 1887 and 1898 there was at least one, and sometimes two. These shows tended to be displays of equestrianism. The width of the main hall allowed plenty of space for the 42 foot diameter ring, deemed the optimum size for an acrobat to stand on a cantering horse. Messrs. Keith, Allen and Quaglieni’s Circus was there in April ‘87 followed by Rowlands in November, and Gilbert’s Circus appeared every winter between 1894 and 1898. But horses and ponies were not the only animals on display. There was a ‘Grand Troup of Elephants’ in Elphinstone’s (also) Grand Circus in 1890, although on the 1st February the visitors may have been more interested in the ‘Exciting Pig Hunt’ as the winner received the pig. In April 1895 Herr Seeth presented seven trained African Lions in a ‘circular iron enclosure’, and a ‘well-bred tiger’ which rode a ‘smart black pony’. The hall did not neglect, between these circuses, its ‘bread-n-butter’ function and skating continued. In the mid-90s there were regular football matches, on skates, and a champion fast skater was engaged to give demonstrations. They also continued to hold banquets and bazaars into the 20th century. In September 1903 the hall temporarily became home to a Dahomey Village. This was a troupe of West Africans, from what is now Benin, which included the famous ‘Amazon’ women warriors who had fought so valiantly against the French a decade before. The Africans showed off - and sold - their Arts and Crafts and gave displays of arms, war dances and songs, half-hourly, admission 3d, 12 noon to 10.30pm. Another warrior tribe used the hall when Keir Hardy MP addressed the local supporters of the Independent Labour Party in 1909, although apparently the hall was not big enough for the crowd. For political balance, in January 1914 the Duke of Portland gave a talk about Irish Home Rule to the Primrose League. The building continued to be used for dances, meetings and functions during the Great War although it was requisitioned twice as a temporary army billet in 1915. After the war and the Victory Ball held there in February 1919, the halls returned to normal but their close neighbour had designs on them. The buildings were sold in the early 20s although the last dancing there was not until Saturday the 5th May 1928. With the loss of the Victoria Halls a replacement was required. This was the New Victoria Hall, at the bottom of St. Ann’s Well Road, which opened in January 1929. This new building still stands [2016]. It became the Locarno and eventually a Bingo Hall.The original building was taken over as additional storage space by Burtons of Smithy Row, the well-known Nottingham grocery company. Since the 1880s Burtons had warehousing in Stanley Place, adjacent to the Victoria Hall, and relocated their headquarters there. They had also excavated 120,000 cubic feet of sandstone from under the buildings to create a cold store, accessed by a large hydraulic lift, and installed ice making machinery. The acquisition of the Victoria Hall made commercial sense and it stayed in their possession until the 1960s when Burtons became part of Fine Foods, one of the first UK supermarket chains, although it was owned by a Canadian. The supermarket disposed of the Talbot Street buildings and in 1973 J. Pullen Enterprises, of the Talk of the Town, Eccles, Manchester, received planning permission for the ‘Conversion of warehouse into theatre club – Heart of the Midlands’. This was despite previous applications in 1967 to use the building and caves as a discotheque or for “worship and religious instruction” being turned down, because of concerns about traffic congestion. The drawings, by Dudding, Middleton and Mutch, accompanying Pullen’s application showed major alterations to the building. Tiers for dining tables, a stage (with pit), suspended ceiling and all the services – kitchen, beer store etc. – were added. Part of the building was demolished beside Stanley Place to provide access for coaches and deliveries. There was even a drawing of the entrance steps detailing the large ‘Heart of the Midlands’ sign.

The club opened on the 6th of November 1973 with Gene Pitney, the American singer, as the headlining act. The intention was for the club to be a membership only, ‘sophisticated’ nightclub with top acts, dining and dancing into the small hours. Unfortunately, the timing of its opening could hardly have been worse. The country was in a bad way, with dire industrial relations, rising oil prices – they even issued petrol coupons, although they were never used - and rampant inflation, which reached 25% by August 1974. For the first three months of 1974 the three-day week was imposed by the Heath government, and the Heart of the Midlands had to cut its prices. The club came through this period but had to lower its sights to survive. The need for membership was watered down. The calibre of the acts, or perhaps their fees, declined. The food became standardised. In 1977, for £6 you could have a reserved table for four plus Chicken Fayre meal, the infamous chicken-in-a-basket. Although this delicacy in plastic ‘baskets’ was derided I wonder how history will view our current fad for serving food on slabs of wood and slate. In February 1978 the venue played host to the first Embassy ‘World’ Darts Championship, organised by the British Darts Organisation. Welshman Leighton Rees won the first prize of £3000. But there did not seem to be enough of these other sources of income and despite having 78-year-old Andy Powell in an Olde Tyme Music Hall as ‘your [1979] New Year present to Mum, Dad or Senior Citizen’ the management wanted out. The baton was taken up by Peter K. Miller who renamed the club ‘The Big Heart’ and relaunched it on the 14th January 1980 with the Nolan Sisters as the top act. Mr Miller, who was based in Barrow in Furness, owning Maxims discotheque there, also ran the Fiesta Nightclub in Sheffield. His tenure in Nottingham was short lived. On Saturday the 12th April 1980, after a show by the Grumbleweeds comedy group, the Big Heart closed. The Fiesta also shut and at a creditor’s meeting in May the dire state of Mr Miller’s finances was exposed. Artistes and employees had not been paid. Booked acts were claiming breach of contract and the thousands of advance ticket holders were trying to get their money back. Mr Miller is alleged to have fled the country owing creditors more than £500,000.

Rock City today. Photo: Keith Fisher.

The club was advertised nationally but, in the end, a local company, George Akins Holdings, who operated clubs and betting shops, took an initial eight year lease from September 1980. The company said that after it had refurbished the nightspot it would provide live entertainment for 20 to 25 year olds. And thirty-five years later Rock City still does.

Keith Fisher

< Previous