Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

EARLY MEMBERS OF THE THOROTON SOCIETY

Thomas Blagg - a founder member of the Society

‘The Thoroton Society owes a debt to Thomas Blagg for the zeal, scholarship and generosity which he so readily placed at its service during his long membership’

Canon R. F Wilkinson. TTS. Vol LII. 1948.

One’s early learning stays well embedded and dies hard. When I was a postgraduate at Newcastle in the 1970s, well before the days of the internet, the publication of the ‘indices and abstracts’ was a great event. With rulers in hand, some academics would rush to the library to measure the length of the index of their publications. We used to liken them to adolescent boys comparing their prowess in the school changing rooms. However, I ruefully admit that when starting to research this article I reverted to this tried and tested, if faulty, method. The result? Blagg, T. M. six and nine sixteenths column inches (16.7 column centimetres for those of you who use a modern version of this technique) in our Centenary Index to the Transactions, 1897 - 1997. A close-run thing but just bettered by Alfred C. Wood and only just ahead of a handful of other prolific contemporary contributors.

In addition to the transcription of numerous church and other records his TTS articles encompassed subjects such as ‘The Manors of Cotgrave’ (TTS 13), ‘A note on the reputed portrait of Robert Thoroton at Nottingham Castle (TTS 44) ... and ‘The Thoroton Society: some memories of its first thirty years’ (TTS 50). He also served as Secretary of the Society’s Record Series, editing volumes I (1903), VI, IX, X & XI (1945).

Thomas Matthews Blagg was born in South Collingham on 5 March 1875, to a family whose links to South Nottinghamshire can be traced back to 1506. Educated at Newark’s Thomas Magnus Grammar School, he inherited a lifelong involvement in the church and an interest in agriculture from his father (another Magnus alumni) and grandfather who was apparently involved in inaugurating Collingham’s annual Agricultural show in the 1840’s and which continues to this day. One rule of his father was to donate one tenth of his income to charity. It was at Thomas Magnus, inspired and encouraged in his interest in the past by his mother, that he developed his research and writing abilities and his painstaking approach in the collection and correlation of data and the piecing together of disparate facts, with palaeography being a particular interest.

He began examining and transcribing Newark Parish Church Records when he was 18.

Twenty-year-old Thomas Blagg (grey jacket). At the first Thoroton Society Excursion 1898. W.P.W Phillimore (with beard) is to the left looking at Blagg. The full image can be seen, courtesy of John Beckett and James Wright, in Issue 103 of this newsletter. He is also present in the other image within that article.

After school he worked as a Corn Merchant in Newark then, shortly after his marriage to Ethel May Haywood of Navenby (Lincs) in 1909 he moved to Buckinghamshire and became a partner in a London genealogical practice and was for many years associated with W. P. Phillimore. His application to the services at the outbreak of WW1 resulted in his posting to the Port of Liverpool as an Inspector for Aliens branch of the Home Office. His subsequent career in the Civil Service earned him an MBE in 1933.

He did not return to live in his native Nottinghamshire until very late in his life, spending his final years at Brunsell Hall, Car Colston (Notts), which had been in his family since 1759 and to which he led a Society excursion in 1908. On his death on 11th August 1948 at 73 years of age, he was the last remaining original member of the Society.

Alongside his Civil Service career, he retained an active and prolific interest in local history, Newark, Nottinghamshire, and the Thoroton Society. He was elected to the Council of the Thoroton Society in 1901 and became the youngest Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1903. Interviewed by the Royal Commission on Public Records in 1915 as the General Editor of the British Records Society, he claimed to have personally examined the registers of over 500 parishes, of which he had transcribed some 300. Writing in Transactions after his death, Canon Wilkinson noted that Blagg was a popular man with ‘a remarkable memory, and an unrivalled knowledge of his native county’ and his scholarship, accuracy and willingness to help and encourage others. However, in the same obituary he observed that Blagg’s occasional brusqueness of manner and incisiveness of speech, hid a very kind and hospitable heart, noting that Blagg did not suffer gladly those he considered to be in error and had never learned an easy tolerance of ‘such common frailties as pretentiousness, indifference or slackness’. Wilkinson also acknowledged that Blagg was ‘well aware of his shortcomings, and that often the twinkle in his eye betrayed the sterner note that his tongue was striking’.

Wilkinson concluded that Blagg was popular with many who knew him well, especially with his grandchildren who visited him daily in his final years.

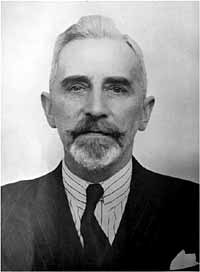

The image of Thomas Blagg commonly reproduced in obituaries and articles. Photographer unknown.

The image of Thomas Blagg commonly reproduced in obituaries and articles. Photographer unknown.As noted by Wilkinson and as you will see, reading various correspondence and between the lines of several obituaries, Thomas Blagg appears to be somewhat like Marmite - your view of him dependent upon which aspect of his character and which side of his tongue you were subjected to.

His approach to local history research and his confidence, perhaps arrogance, was publicly revealed when in February 1906 the Nottingham Guardian reproduced a series of letters that had appeared in the Daily Express. A fellow Society member had written to the Express to criticise documents that were distributed to support work on the ‘Domesday of Enclosures for Nottinghamshire’(a reprint of the agricultural inquisitions of 1517) in the ‘Transactions Pamphlets’ of 1900 and 1902. To which 30 year old Thomas Blagg issued a blistering riposte that included - ‘The historical school of which Mr Stapleton is apparently a survivor, that which is content with mere recording of names, dates, and events - work which is largely a vanity and vexation of the spirit, without profit under the sun - has now been replaced by modern scientific students, who, removing historical study from the stagnant waters of

dilettantism, have rightly sought to show that history is the science by which we read the causes and processes of past and present social and economic evolution, the key by which we may to some extent unlock the mystery of the future if we only, with knowledge, read, mark and inwardly digest the records of the past.’

Stapleton had also complained about the pages of statistics included in the circulation, describing them as ‘padding’, to which Blagg countered that the publication without the tables ‘would resemble the publication of a foreign treatise without translation, or a directors report without the balance sheet, or of a book of travel without the map’.

A further letter from ‘a member’ sided with Stapleton and another with Blagg. This exchange reveals an important point in what was later alluded to and as revealed by the changing contents of the Transactions, as a tension between those who enjoyed a Society of excursions and expeditions to which papers were read and those who desired a Society which promoted articles that would form a growing corpus of knowledge of Nottinghamshire. It is not known to what extent this exchange influenced Stapleton’s decision to emigrate to Australia where he died. However, a short local obituary for Stapleton in the same edition of the Nottingham Guardian noted that there was in Nottingham a lack of material appreciation of his merits.

A letter from the Secretary of the Thoroton Society Council in December 1934, asking on their behalf whether he would take over as Secretary of the Records Section may also reveal his less than universal popularity within the Society as Blagg wrote to a friend and confidante from the Council, Mr Lehman, that it consisted ‘of eight lines only and might have been written on the Ides of March or any other non-existent date, instead of written a day or two of Christmas ... in fact it is the only ice I have seen so far this winter!’ In the same letter he confided concerning this request: ‘Heaven knows, I wanted no further burden than those I already carry, but I fear that If I crave to be excused I shall be thought to have shirked the consequences of my own action and this most desirable project may die of inattention at birth’. However, he had previously outlined to the Council how the Records Section should be reformed. As requested, he refined his proposals to ‘get the records section working’, which he travelled from his home in Birkenhead to present to the Council at the end of January 1935.

Christmas 1932. Photograph James Bacon & Sons, Liverpool. Courtesy of National Civil War Centre and Newark Museum.

Christmas 1932. Photograph James Bacon & Sons, Liverpool. Courtesy of National Civil War Centre and Newark Museum.To conclude, an obituary in the Newark Advertiser noted him as a ‘wise counsel’, ‘kindly but firm’, and of a jovial nature, ‘those who could claim his friendship or even an acquaintanceship counted themselves fortunate’ as I am sure the some in the Society did (and some seemingly did not) and those who know of his lasting contribution still do. Oh yes. Obituaries included Newark Herald 14th August 1948 - 65 column centimetres (25.6 column inches) and Newark Advertiser 18th August - 124 column centimetres (48 column inches).

Sources include; Thoroton Society Transactions (esp TTS 50 and Index), Collingham Village Archives, photograph and various obituaries held by Newark Library also the National Civil War Centre and Newark Museum, Letters and various documents held by Nottinghamshire Archives.

Also, Phillimore. W.P.W. County Pedigrees. Nottinghamshire. Vol 1. (London Phillimore. 1909).

Jeremy Lodge.

< Previous