The lost manor of Kirkby Hardwick

by Trevor Lewis

Remaining long stone wall. Photo: Alan Kirk.

Introduction

The Kirkby & District Archaeological Group (KDAG) is only recently formed (2010) but rapidly, and unexpectedly, found itself engaged in supporting two phases of archaeological investigation in October 2011 and March 2012 on the site of Kirkby Hardwick Manor, which was demolished by the National Coal Board in 1966.

The Group’s initial aim had been to follow up the discovery of a Neolithic axe-head on the eastern edge of Kirkby-in-Ashfield, using a field-walking project to see if there was more evidence of ancient settlement. This proposal was put on hold when it emerged that Mrs. Betty Kirk - a former resident of the house - had for some years been urging the authorities to undertake an excavation at Kirkby Hardwick. An application was made for Local Improvement Scheme (LIS) funding to Nottinghamshire County Council, which proved successful. In the meantime, the Committee (without much historical knowledge or research experience) started to find out about the site through visits, by acquiring historical information (not least G.G. Bonser’s article in Transactions, 1912), archive material, maps and photos, and by recording the memories of others who lived at the house in the 1930s to 1960s.

Context

Drawing of internal west and north interior walls by Samuel Hieronymous Grimm, 1773 British Museum.

Photo 1880 of exterior north and west walls. Manuscripts & Special Collections, University of Nottingham.

Photo 1880 of exterior north and west walls. Manuscripts & Special Collections, University of Nottingham.The site is 100 metres west of Sutton Parkway train station on the Robin Hood line.

Above ground little remains to be seen of the ancient manor house and its successors; only a long, thick stone wall with brick infill and few features, and a patch of modern quarry tile flooring in an outbuilding.

Grimm’s very accurate drawings from 1773, along with photographs from 1880 until demolition, reveal something much grander; a second storey with late-medieval or Tudor windows, fireplaces and chimneys; also more extensive walls with loop-holes enclosing the site to the east and south.

If these pictures hint at a building of considerable status and interest, the emerging history confirms it as a place worthy of re-discovery and extensive investigation. To an unusual degree the site encapsulates a national story from pre-historic beginnings to a post-industrial conclusion.

- a pre-historic flint core discovered on site in the course of the October 2011 excavation

hints at ancient settlement close to the source of the River Maun - the earliest mention comes in the Sherwood Forest perambulation of 1232

- there is a series of powerful owners: Sir Richard Illingworth, the 4th Earl of Shrewsbury; the Dukes of Newcastle – powerful enough to avoid inclusion within the Forest boundary, (though the dovecote is included)

- it provides one night’s lodging for the disgraced and dying Cardinal Wolsey

- dereliction sets in, probably the outcome of Royalist ownership in the Civil War

- recovery of the manor by the Duke of Newcastle after the Restoration

- tenanted by yeoman farmers (Clarkes) for 300 years – we have Thomas Clarke’s diary and

Samuel Grimm’s drawings from the 1770s - enclosure of surrounding common land

- the Industrial Age arrives: Nottinghamshire’s first ‘railway’ (horse drawn from Pinxton to

Kirkby, then free-wheeling to Mansfield via Kirkby Hardwick) opens in 1819 - hay ricks are burnt, supposedly by local Chartists

- the house has a mid-Victorian makeover, with mock-Tudor windows modelled on the ancient

remains - 1880s: Summit Colliery opens; spoil starts to spread towards Kirkby Hardwick; a brick works

is established and railway sidings obliterate the fish ponds - purchase by the National Coal Board to avoid expensive compensation for subsidence and

spoil spread; the house is divided up and leased - demolition comes in 1966; the local authorities don’t value the Manor as local heritage;

visitor ‘safety’ is cited as a reason to demolish the medieval as well as the later structures - the spoil heaps are landscaped and planted up; dog-walkers create a network of paths

- late 20th – early 21st century: a rise in interest in genealogy, heritage and archaeology: the

past is valued again - 2011 – 2012 sees excavations and a desk-top study to re-discover Kirkby Hardwick, with the

longer term aim of conserving the ancient walls and creating a genuine “Local Improvement’

in the environment for the benefit of Ashfield residents.

Questions in search of an answer

Sherwood Forest map of the late 15th or early 16th century. British Library.

Summit Colliery: aerial photograph 1948 Sites and Monuments Record Kirkby Hardwick can be seen on the extreme right centre of the photograph, arrowed.

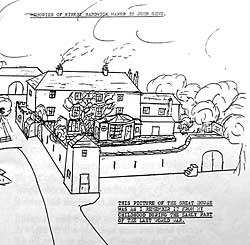

John Gent drawing, early 1940s: his memory of Kirkby Hardwick. Permission from Elaine Scotney.

Despite many references to Kirkby Hardwick in documents from the 13thC onwards (where it is also referred to as Sutton Hardwick, Hardwick-upon-Line, even Hardwick Hall) the first date when we can be certain that the site includes a significant residence in 1530, when the 4th Earl of Shrewsbury lodges the dying Cardinal Wolsey after a 25 mile ride from Sheffield Park on a mule. Of course it is highly likely that there was living accommodation from much earlier, rather than a mere land-holding, but this is just one of the gaps in our knowledge that requires filling with solid evidence. There are plenty of others. The house we know from later maps and photos stands within, and largely separate from, the late-medieval walls and has gone through several modifications, but we lack any certainty about their dates and extent. Persistent rumours also exist of a chapel at Kirkby Hardwick, and of lead coffins buried in the grounds, as well as cellars, passages and the inevitable (and well-attested) ghosts.

Disappointingly, of course, the archaeologists are more concerned with sober realities than the more romantic and lurid possibilities of the site: finding bodies is a hazard to be avoided, not embraced. The excavation is labelled ‘an evaluation’: only the upper strata of the site are to be uncovered and a major objective is to establish just what has been left after the demolition process. Has the archaeology been wrecked beyond the possibility of useful investigation?

The excavation: Phase 1: 3-15 October, 2011

The Nottinghamshire County Council archaeologists were committed to the Project: David Budge (in charge), Emily Gillott and Andy Gaunt. They proved excellent in dealing patiently and expertly with interested members of the public and some 35 volunteer diggers, many of whom were new to excavation.

Some aspects of the organisation were the responsibility of the Project Manager at County Hall but KDAG was heavily involved in developing the community aspects of the dig: recruiting volunteers, arranging for visits by schools and a day centre, meeting with local residents, commissioning a video and photographic record, and seeking extra funds. VIPs, including Councillors and Ashfield MP, Gloria de Piero, visited the site on the 2nd Friday and an Open Day was held the following day. This proved unexpectedly popular, with over 60 visitors to the site, and brought us new information from local families, including a drawing of Kirkby Hardwick in the early 1940s.

The site required two days of preparation with chain saws and a mini-digger to clear a minor jungle of self-set trees, shrubs, and dumped rubbish. Four trenches were opened over different parts of the footprint of the final house, along with an existing drainage ditch which had been cut through its south side, exposing some of the archaeology. The whole area is covered by spoil from the colliery to varying depths.

What was achieved?

Location of the six trenches. Alan Kirk.

We await David Budge’s full report, but he has provided the following summary:

"‘The evaluation excavations at Kirkby Hardwick were very successful. They answered many of the questions they had been designed to address and revealed a variety of information about the site and its history. In particular they:

- demonstrated that destruction of the last phase of building on the site was not as complete as feared; walls have survived 4 or 5 courses high in parts

- revealed that good evidence for phasing exists in the remains of the final structures to stand on the site. For example, in the west wing of the house it appeared that an original (though not necessarily Tudor) stone built structure was modified at a later date by the insertion of a corridor and then brick-built cellars

- found evidence of late-medieval or early Tudor activity lending weight to the theory that the original Tudor house may have consisted of three wings around a courtyard

- were not able to eliminate the possibility that the ‘garden wall’ to the south west of the house could be Tudor (which, if it was the case, would suggest the structure was a gigantic house or palace)

- revealed the earliest evidence for human activity on the site, in the form of a prehistoric flint core

- demonstrated that the site has a high archaeological potential and that further investigation would be likely to reveal a wealth of information relating to the development of an important great house of Nottinghamshire from at least late medieval times onwards."

Postscript

In a further article we hope to report on phase 2 of this project following a further period of excavation which took place between 19 March and 13 April 2012 which greatly increased our knowledge of the house – not least in the discovery of pottery which pushed the site occupation back to the 13thC and prompted a major rethink about its earliest shape and development.

In the meantime KDAG continues with the desk-top study, grappling with unfamiliar legal terminology, researching the Clarke genealogy and hoping to complement the archaeology with archive discoveries. A lively 25 minute video of phase 1 is now available, price £6.00 from 01623-755156.