Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

The Dako Boys

By Rachel Farrand

The UK National Inventory of War Memorials (UKNWIM) lists nearly 1,000 memorials in Nottinghamshire, a list which is not exhaustive. The database includes memorials which have either been lost or known to have been destroyed.

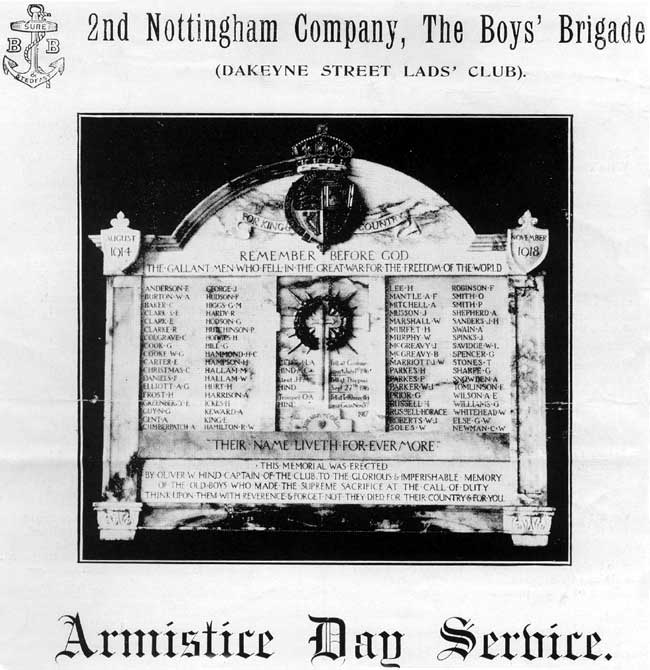

One Nottinghamshire memorial, known to have been destroyed in the 1990s, was raised by Oliver Hind, a Nottingham solicitor and philanthropist, to over 70 former boys of the 2nd Nottingham Boys' Brigade Company who died in the First World War.

Hind, a territorial army officer, had joined the Boys' Brigade in 1901 and was put in charge of the 2nd Nottingham Company, which met in premises on Rutland Street, in 1905. Hind was ambitious for the Company to increase its numbers, to be able to offer a greater range of activities and to open nightly and, by 1907, he had acquired more suitable premises in Dakeyn Street, in what had once been part of the county asylum. The building became known as the Dakeyn Street Lads' Club and the boys, aged between 12 and 17, who were expected to observe the regulations and wear the uniform of the Boys' Brigade, were popularly known as The Dako Boys'.

Research into the names on the memorial has highlighted an interesting piece of Nottingham's social history. In 1908. Hind informally helped two members of the Company to emigrate to Canada and by 1911 had assisted 12 boys to make a new life in the Dominion. In 1913, inspired by the success of these old boys whom he had met on a visit to Canada two years earlier, Hind, with the financial support of J.D. Player, bought and set up a 270 acre farm (Dakeyne Farm) at Falmouth near Windsor in Nova Scotia, where boys would spend a year learning a range of agricultural skills. Hind's scheme was recognised by the British and Dominion authorities as a juvenile migration society and between 12 and 15 boys, all with the permission of their parents, went out each year to Canada. Ownership of the farm was transferred by Hind and Player to the National Association of Boys' Clubs in 1929 by which time several hundred Dako Boys had travelled unaccompanied to Canada to start a new life.

At least five men named on the memorial are known to have gone out to Canada and subsequently to have served in the Canadian infantry. William Burton, age 17, sailed to Canada on the SS Virginian, arriving in March 1913. He attested on 11 November 1915, joined the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles Battalion and was killed on the Western Front in September 1916. Frank Tomlinson was 19 when he left England, sailing on the SS Canada to arrive in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in April 1912. The ship's passenger list suggests that he travelled out with six other Dako boys. Tomlinson joined the Canadian infantry (Manitoba Regiment) in December 1914 and was killed in France the following October. Another boy, George Williams, went to Canada in 1911 at the age of 17; the 1911 census for Nottingham records a brother aged 16 and a mother who was a widow. Williams enlisted in the Canadian infantry (Saskatchewan Regiment in January 1915 and was killed in France in 1916.

Burton probably trained at Dakeyn Farm, but as the farm did not open until 1913, Tomlinson and Williams may have been among the earliest group to have been motivated to emigrate by the example of the first two migrants and whom Hind also assisted by arranging their passages and employment in farming on their arrival in Canada.

There is much more work to be done to put together the stories of these young men who made the decision to leave England in the hope, or perhaps expectation, of a better future in Canada. Juvenile migration, particularly that of young children through schemes which continued into the 1960s, has been the subject of much research, scrutiny and adverse publicity in recent years. Oliver Hind's scheme, though, was directed at young men who came from a densely populated, impoverished area of Nottingham, with inadequate school facilities and only the prospect of low paid, insecure and unskilled work. It was, perhaps, a natural progression for Hind whose vision for the Lads' Club was to provide boys with 'activities that would tend to cultivate their talents and enable their minds to develop through which 'it could be made possible for them to break out of their predicament and enter a more desirable role in life which might contain a prospect of further advancement and development'.