Book reviews, Spring 2013

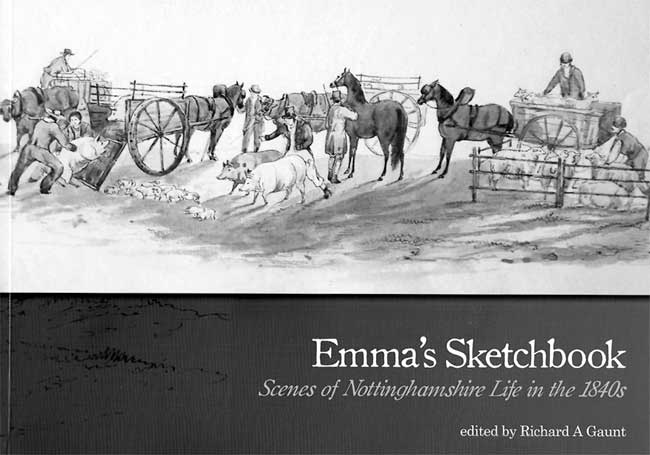

EMMA’S SKETCHBOOK, SCENES OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE LIFE IN THE 1840S.

Ed. Richard A. Gaunt. Nottinghamshire County Council, 2013. ISBN: 978 0 902751 74 3

The Emma of the sketchbook is Emma Elizabeth Darwin (1820-1898), daughter of Sir Francis Secheveral Darwin and his wife Jane Harriet Ryle.

She was a cousin of the Victorian polymath Sir Francis Galton and half-cousin of the naturalist Charles Darwin, their shared ancestor being their twice-married grandfather, physician and poet, Erasmus Darwin of Elston Hall. In January 1842 she married Edward Wilmot, land agent to the 4th Duke of Newcastle at Clumber, and son of Sir Robert Wilmot (3rd baronet) of Chaddesdon. Emma excelled in one of the ‘accomplishments’ expected of the middle class lady of her time, she was an artist of some distinction.

Dr. Gaunt has specialist research interests in the use of biographies, diaries and autobiographies, is a noted authority on the 4th Duke of Newcastle and maintains a scholarly interest in the cartoons and caricatures of the age. This expertise he uses to furnish thirty or so pages of valuable historical context to the world of Emma and her husband, and which provides an adsorbing introduction to this collection of fifty of her drawings and watercolours of Nottinghamshire in the first five years of her marriage, 1842-47.

Social problems dominated the economic and political scene in the 1840s. Food prices were high, a depression threw many people out of work and there was turmoil in response to the rapid changes that came with industrialisation. We can detect little or nothing of this in the drawings of Emma Wilmot and, in its place, we are treated to quiet depictions of architecture, nature, animals and rural life. There are familiar local landmarks such as Clumber Park, Welbeck and Newstead Abbey, Cresswell Crags, Worksop church, Manor and Priory as well as the, now disappeared, Blyth Hall (p.60), demolished in 1972 to be replaced by up-market housing. There are two remarkable drawings of Steetley chapel in ruins (pp. 75-6), before its restoration in 1880. When Emma came to see this amazing example of Norman architecture, it was decayed and almost hidden by foliage. She illustrated the porch and the celebrated triple arch of the roofless chancel. There are three drawings of Worksop Manor as it was being demolished (pp. 65-7). The Duke of Newcastle had bought the estate in 1838 and Emma recorded the transformation, as the Duke sold off the windows, doors and roof of the house and then blew up the walls with gunpowder.

At Newstead she drew the abbey’s south façade, from across the Leen, and then the elaborate sixteenth-century octagonal fountain in the cloister garth, with its grotesque figures, Immortalised in Byron’s Don Juan,‘here perhaps a monster, there a saint’ (pp. 57-8).

On the inside front cover, it’s a surprise that the view down Sparken Hill, through the trees looking north towards Worksop, has hardly changed in one hundred and seventy years. Agricultural practice has changed; a mixed team of horses and oxen apparently groom a pasture with a drag harrow (p. 44), a group, including bonneted women, harvest carrots with long-tined forks and trim them, perhaps for over-wintering in sand (p.47), and turnips are sown with a double-tube seed-drill (p.48). Drills were expensive and, despite being invented long before, were perhaps only just coming into general use in Nottinghamshire. If there is any turmoil, it is at Langwith by Warsop in September 1842, where a magistrate on horseback and brandishing a whip, gives chase across the fields (p. 410. But are the retreating figures that he pursues, Chartist agitators or simple poachers; we are not to know?

Emma’s sketches are of considerable charm, and show her interests lay in landscape, animals and architecture. Her ‘pleasure of ruins’ and the relish she takes in crumbling structures and trees is evident. Her human figures seem little more than incidental details in the scene, usually shown in profile, with faces often obscured by bonnets. If there are any more sketchbooks of her work, they have yet to be found, but it is surely inconceivable that she ceased to draw and paint in the 1840s; she lived for half a century more. Forty years later, in April 1882, we know she was present at the funeral of her kinsman, Charles Darwin, in Westminster Abbey. Perhaps a further sketchbook waits to be discovered. It would be fascinating to see what Emma made of that occasion as she and the Darwins, the Galtons and the Wedgewoods mingled with Hooker, Huxley, Alfred Russell Wallace and the great and good of the Victorian era.

Dr. Tom M. Smith.