Book reviews, Spring 2023

Elizabethan wall painting in the Saracen’s Head Hotel, Southwell

Authors: Members of Southwell Community Archaeology Group, edited by Dave Johnson and Andy Weaver

ISBN: 978-1-9161003-1-2

This is the long awaited account of the research done by members of SCAG, with expert support, on the wall-paintings in this hostelry which is at the heart of Southwell. Despite being in a well-known and central position, these amazing paintings went more or less unknown to many, including much of the local population. SCAG sought to bring them to light by undertaking a role in the Vernacular Buildings Project, funded by English Heritage (now Historic England). In 2017 SCAG was granted a generous sum from the Thoroton and Geoffrey Bond Research Awards to enable the research project to continue, now with the support of experts in the field. This has resulted in this excellent, well-illustrated book. The book takes us through the history of the hostelry, the likely date of the paintings’ creation - the late 16th or early 17th century - the time when the country was beginning to recover from the religious turmoil caused by Henry VIII and subsequently by his children. It stresses the importance of the paintings, not only because of their quality but in that they are one set of only three in the county, both the others in Newark. This is an excellent publication. It had been hoped that an account of the project and its outcomes would appear in the Transactions but unfortunately this was not possible - this book fills a gap in information on this important and unique part of the county’s history. SCAG presented the Society with a copy of the book in acknowledgement of the grant given towards this on-hands research project.

Barbara Cast

Baku to Beeston

Hilda Stoddart and Neil Cossons

ISBN 978 1 3999 2636 2

One of our Vice Presidents, Sir Neil Cossons, has written a book based on the letters home of his father, Arthur Cossons, during the First World War. Below John Beckett’s review of this book.

Arthur Cossons (1893-1963) was well known to older Beeston people from his time as headmaster of Church Street Junior Boys School. He is described in the Illustrated Guide to the Blue Plaques compiled by the South Broxtowe Blue Plaque Group as ‘an enthusiastic historian and pioneer of local history’. In the First World War he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and served both at home, and overseas on the Eastern Front. His two children, both brought up in Beeston, have combined to produce this edition of Arthur’s letters home 1917-19 when he was on active service with the RAMC in the Salonika campaign fighting the Bulgarians and their allies in the Balkans. Sadly, Hilda died in 2015, so Sir Neil has completed and edited the book.

The book commences with a brief biographical account of Arthur Cosson’s life. This was originally published in Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 113 (2009, 105-18, particularly pages 107-8). This is followed by selected passages from the letters, illustrated with photographs and postcards sent by Arthur, and watercolours painted by him. The letters came to light after Arthur’s widow died in 1986. There were 164 letters. Hilda transcribed them all although only excerpts from them are published in the book, the choice largely depending on what light they throw on Arthur’s life in wartime. Basically, he wrote about those matters that the censor would allow through! Thus, the first letter in the collection, dated 19 October 1917 is headed ‘somewhere in Italy’. Most of the letters are addressed to his mother, probably with the expectation that they would be passed on for wider reading within the family and they are relatively low key. He writes about the weather and food, as well as occasions and events, among them Christmas Day and a wedding he witnessed while out on a walk. He also writes about his job in the corps. He is scrupulously careful not to give away information which might lead to identification.

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 made little difference to Arthur, partly because he was in Salonika on the eastern front, and also because his medical work continued unabated. But by January 1919 he was considering his options for the future. The following month he was thinking wistfully that ‘perhaps it will not be so long, after all, before I am home’ (p. 99). By 11 February he was on his way home, but this was going to be a long and tedious journey and in August 1919 he told his mother that he had extended his army engagement for a few months. It was not until February 1920 that he boarded a homeward bound vessel, and it was only in March that he was discharged, a reminder that the war did not end for many servicemen on 11 November 1918. Arthur was a native of Taunton but on his return to England after the war he trained as a teacher and in 1922 he was appointed to Church Street Boys School in Beeston. The town was Arthur’s home for the rest of his life. He was an air raid warden in the Second World War. He died in February 1963.

Neil is not selling this book but John will be happy to lend it to any Thorotonians who would like the opportunity to read it.

John Beckett

Inclosure 1845-1865 of Nottingham’s Fields

June Perry (June Books, 2022)

ISBN 978-1-3999-3350-6

For a number of years (interrupted by Covid) June Perry organised the annual Greater Nottingham Enclosure Walk from the south end of Queens Walk to the Forest, usually on the first Sunday in July. The walk is intended to commemorate the Nottingham enclosure act of 1864 and the subsequent enclosure award of 1865. June is a Friend of the Forest and she took the view correctly, that the importance of enclosure in promoting the development of Victorian Nottingham had been underestimated. June also went off to Nottingham archives in search of any relevant material. Much to her surprise she found masses of documentation, notably the twenty volumes of enclosure commissioner’s minute books which she spent many hours transcribing.

The finished result is this book, 678 pages long. The material is divided into 44 sections (or chapters) covering all aspects of the enclosure from the first discussions of the need for enclosure to the completion of the award. In each section attention is paid to different aspects of enclosure. Quotations from the different volumes of the enclosure commissioners are included, images- both contemporary and modern- help to enlighten the reader about the many aspects of enclosure.

It is a veritable tour de force in terms of the hours of work which she has devoted to the project. But having said all of this I must throw in a caveat: the book is very difficult to navigate. The problem is simple. The book lacks any foot or endnotes, or bibliography or index. Working through the material, is as June recognises, complicated.

There is simply too much detail, a point June recognises when she suggests that readers should not feel bound to read every word! Much will depend on the individual reader but with 678 pages and roughly 20,000 words to plough through there is bound to be some corner cutting. In other words, in an attempt to stop the book becoming even longer, June has left the readers with no way of following up issues that they might just want to learn more about. Put in another way the book gives the impression that no one else has ever researched and written about the Nottingham enclosure and future researchers will have no means of shortcutting from her book to investigate further, except by guessing where to start from her 44 sections. To give an example, section 31 p.271 is headed ‘Requests for land’. This is not surprising since the enclosure commissioners had to sell land to raise cash to put the enclosure into operation. But no context is offered. Who was Mr Orange, and what was the land saving bank that he represented? A little further research would have revealed that he was James Orange and that the land savings bank was an organisation which set out freehold land estates, one of which was Southey Street.

Inclosure is an important book, both for historians of Nottingham and historians of enclosure. It is a book to be kept on one’s shelves and consulted frequently over time, and will be annotated regularly as I work through different questions about enclosure!

John Beckett

ARTICLE REVIEW

Pete Smith, ‘Plumptre House, Nottingham: Colen Campbell and John Plumptre’, Georgian Group Journal, xxx, 2002, 37-70

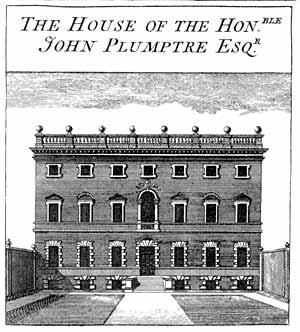

Plumptre House, c.1750.

Plumptre House, c.1750.During the 17th century, the country underwent a major upheaval, suffering a civil war which resulted in the death of Charles I and the establishment of a Commonwealth under the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. However, the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 returned Charles II to the throne. This brought about great changes and inaugurated a more flamboyant and prosperous society.

Nottingham played a major role in these events, beginning with Charles I unsuccessfully raising his standard at Nottingham Castle in August 1642; later, the town and the castle became major parliamentary strongholds. Sadly, Nottingham Castle was slighted at the end of the civil war and its ancient fortifications were demolished.

The restoration of the monarchy resulted in many local gentry returning from exile to take up residence in Nottingham once again. The most famous of these was William Cavendish, who purchased the ruins of the castle and built a fine ducal palace which overlooked the town and neighbouring countryside.

Across Nottingham, on land that had once witnessed its origins as a Saxon settlement, the gentry brought new wealth and ideas to the area. Families like the Plumptre and Pierrepoint families purchased land and built fine houses incorporating large gardens in which to enjoy their new lives under the Stuart kings. Today, the Lace Market area is filled with old red brick factories which tower above the streets as you walk along them. Most people do not realise that this is where Nottingham began, let alone know about the fine architecture which once adorned the area before industrialisation came to the town during the 1800s. In the 18th century, visitors sang the praises of the splendid buildings in this area. For example, Daniel Defoe famously described Nottingham ‘as a fine garden town’.

In a new article by Pete Smith, ‘Plumptre House, Nottingham: Colen Campbell and John Plumptre’, the author explores the design and construction of one of the finest buildings in Nottingham, Plumptre House. He examines the work of its architect Colen Campbell and considers the way in which John Plumptre involved himself in his own ‘grand design’ by determining the interior layout of the house.

The article is profusely illustrated with original plans, maps and drawings of the house, many of which are held in Nottinghamshire Archives. These show how Plumptre House dominated a large area adjacent to Stoney Street. Badder and Peat’s map of Nottingham (1744) clearly shows its location to the side of St Mary’s church, giving a grand view of one of the town’s principal buildings. The garden to the rear of the house was also extensive, its length running parallel with Stoney Street. The area around St Mary’s was one of the most prestigious in which to live and many other fine houses in the vicinity enhanced the grandeur of this part of the town.

Pete Smith provides a fascinating insight into the building of the house but principally the way in which Colen Campbell and John Plumptre worked together to achieve their joint enterprise. The article also provides an insight into the role of the Plumptre family and their place in the history of Nottingham. However, the author offers more than the story of a house from its origins to its demise. He shows how ‘an amateur draughtsman and architect’, who had a dream of what he wanted to create, came to choose an architect with a good track record whom he trusted and how, together, they fulfilled that dream in the heart of Nottingham.

Sadly, today, Plumptre House is no more and the family is no longer prominent in the town; John Plumptre’s descendants later left Nottingham and moved to Kent.

Kevin Powell

Nottingham Civic Society